Way too many people don’t take teachers seriously. Teachers have massive educational requirements, several hundred years of history as one of the major recognized professions, and they provide a service so valuable to the health of society and the needs of the economy that even in the U.S.—land of what can we privatize next?—there is a certain sanctity, at least among liberals and leftists, to the idea of free public education for all. Private education options predate public education, and have persisted and flourished along with public education. So in a way, when defenders of public education talk of the opposition as being bent on privatization, this is a bit of a misnomer. Even Betsy deVos (Trump-appointed U.S. secretary of education) probably doesn’t want to completely do away with public education; rather, the right-wing agenda, and the left-wing education reform agenda (similar in many respects), is subtler than that. It’s a combination of sharpening the divide between “bad” public schools and “good” private schools, while using private philanthropy to allow a few of the most underserved students—those with particular merit according to whatever random metric is in fashion—to avail themselves of this higher quality product. In other words, to put it crassly, it would be un-American to not assent to free public education, but no one said it had to be quality education. (Yes, this is a big oversimplification, but there isn’t space to get into the complexities.) One of the persistent beliefs on both sides of the education reform battle is that private schools, whether religious or not, charter or not, for-profit or nonprofit, will be staffed with non-union educators. But is this necessarily the case? We’ll get back to that in a minute.

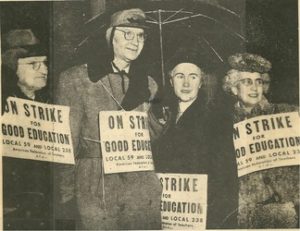

Teachers are also one of the classes of public employees that have been organized into unions for the longest time. Along with other public employees unions, teachers unions have suffered some loss of power since at least the Reagan years and the seismic effect of the destruction of the PATCO union. (For those unacquainted with 1980s labor history, this was a union of highly paid air traffic controllers that was “broken” by the Reagan government when they struck for better working conditions.) In Chicago in 2012, however, the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) made history when in its first strike in 25 years, it made huge gains against Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s school board with a seven-day walkout. To many, this signaled a possible turnaround in the balance of power for teachers and maybe for other public employees too. In addition to that, the CTU strike, along with the processes leading up to it and its aftermath, became a famous case study, which showed how to organize, as well as the superiority of organizing over mobilizing to achieve actual shifts in power. The story is best elucidated in Jane McAlevey’s book “No Shortcuts—Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age.” Crucially, the CTU strike was not primarily about wages; in fact, it was sparked in part by the offer of a larger than usual pay hike, in return for teachers not opposing massive layoffs. It’s a mark of how neither teachers nor unions were being taken very seriously in 2012 that a seasoned political op—and a Democrat—like Emanuel would think to use divide-and-conquer in the face of a culture literally built on the idea of solidarity or death. Other issues raised included reducing class sizes and rolling back standardized testing. In other words, the CTU had a holistic political agenda for education, of which their personal salaries were a very minor piece. Another smug assumption and miscalculation on the part of the school board was that parents would be opposed to the strike and unwilling to put up with any personal inconvenience. The school board and the powers behind them were shocked that parents supported the strike wholeheartedly, doing solidarity pickets, watching each others’ kids, and performing other strike support functions. This is because, in the organizing model correctly used, the teachers would have spent months educating parents on their agenda and how it would benefit their children and their families, and calling the strike would be predicated on knowing that they had that support. Since the 2012 strike, support among the public for CTU has remained strong, while there is negative support for the school board. It’s worth noting a couple of things about the Chicago Public School system—first, its board is entirely appointed by the mayor, not elected like most school boards in the U.S. And second, the board has been wracked by scandals continuously, including the guilty plea of the previous “CEO” of the board for fraud in a multimillion dollar bribery case.

Chicago’s school system has less than 10% white students. By contrast, the state of Wisconsin has over 60% white students in all of its school districts, and even the city districts, which have the highest percentages of students of color, are majority white. While this makes racial gaps in education measures a major issue for Wisconsin, the two school systems have in common a history of being deprived of resources, though for ostensibly different reasons. In 2011, the state legislature of Wisconsin passed the notorious Act 10, which severely restricted collective bargaining rights for teachers unions. This was on top of a super-fiscally-conservative funding formula that had already been starving public schools since the 1990s. The aftermath of Act 10 has been devastating to the teaching profession in our neighbor state, and provides an object lesson in what happens when teachers are devalued and de-professionalized. Carol Trone, writing in “The Progressive,” says, “In poorer districts the result has been an unprecedented fluidity in their teacher workforce. Years of underfunding had already left poorer areas of the state bereft of the resources to keep more experienced teachers. Without the healthcare, retirement, pension, and tenure protections from collective bargaining, there was even less incentive for teachers to remain in lower-paying districts. The workforce shift—in a profession characterized by longevity—has been dramatic. $900 million dollars were drained from Wisconsin teachers’ collective wealth and with it the spending power that sustained their families and their communities’ economies.”

It looked for a while like Saint Paul was about to take a leaf from Chicago’s book and have a game-changing teachers strike. It would have been their first strike in 72 years! 85% of the membership was in favor of a strike if the negotiations failed, and, like in Chicago, the Saint Paul Federation of Teachers (SPFT) had laid the groundwork and was confident of community support. Maybe the tide is perceived as turning, at least here in the upper Midwest, but the school board settled just in time to avert the strike. Meanwhile, in a state far away, but with more in common with Wisconsin than with Illinois, (It’s a “right to work” state for one thing) a teacher strike that lasted nine school days has made major waves. West Virginia has the third lowest paid teachers in the country, but still, base pay was not the only or even the primary goal of their strike, unlike their only previous strike, as recent as 1990, which was not particularly successful. Other major goals include opposition to bills that would lessen the effects of seniority in transfers and layoffs, and mostly importantly, a long-term solution to the fiscal crisis of the state fund that provides for their health insurance. Although full credit must be given to the WV teachers union for the extent of their organizing—including a nationwide outreach for support, a coordination between all 55 counties in the state for total solidarity, and the union working with charity providers to cover the food and non-education services normally provided to low-income students—part of their notable success compared to 1990 is just structural: As in Wisconsin, with such low salaries and benefits, many teachers have left the state or the profession, and there is a critical shortage of teachers. The union leaders initially moved to settle based on the governor’s promise of a 5% pay raise, but rank and file stayed out an additional three days, over a tense and busy weekend for strikers, lawmakers and media commentators, as the two parts of the legislature tried to whittle it down or claimed they would have to slash Medicaid to fund it. But that was never going to happen. Teachers and other support staff knew that if they didn’t blink, they would win, and so they won. Most schools re-opened Wednesday, March 7.

Meanwhile, in the world of union organizing, there is another trend that has been going on in the last half-decade as unions in the U.S. make their resurgence, and that is something Southside Pride has covered elsewhere: the moves to organize worker groups that had been previously considered impossible to organize or not worth the effort. There is a societal redefinition of the working class that is picking up those from “below,” such as contract janitors, security guards, home health aides and construction day laborers, and those from “above,” such as graduate student workers, workers at food cooperatives and, perhaps next, teachers at private schools and academies. In New York and California, and other areas, teachers unions are moving into non-traditional and non-public schools with some success.

Chris Baehrend is a union member and a teacher at a charter school in Chicago. There was no union in the tiny struggling charter school when he started, but he and fellow teachers saw the need and created one. Later, they merged their union with CTU. In a Chicago Tribune article titled “How Unionized Charter Schools Benefit Public Education,” he writes: “If you trust teachers, then you should trust their democratic voice—their union. Unions make schools, both district and charter, work better.” When Minnesota’s food co-ops began experiencing a wave of organizing drives, most of their hired management and elected boards of representatives realized that a union was not necessarily a threat to an organization that is already created in the name of democracy and public service. Here’s hoping the charter, parochial and non-traditional schools, which have been such a big part of the education picture in our state, come to a similar conclusion.