Journal entry on CaringBridge by Connie John (Polly’s daughter)— Jan. 19, 2023

Journal entry on CaringBridge by Connie John (Polly’s daughter)— Jan. 19, 2023

It is just over a week ago that I woke up about 4 a.m. and heard Mom wheezing. I got up to see how she was doing. Mostly after the stroke when she could not be trusted to chew food and swallow, we gave her blended food and drink in “sippy cups” that are made for toddlers as this worked better than spoon feeding. I gave her water and a bit of food in a sippy cup and albuterol for the wheezing. She seemed to feel better, and I went back to bed and thought that she was sleeping more soundly after that. But when I checked on her at 7:45 a.m., she was no longer breathing at all! Mom wanted to donate her body to research and that is what was done. The next day we arranged for representatives from the University of California, San Francisco, to pick up her body.

Although she was not entirely “herself” before the stroke, we had lots of good times together playing games and reminiscing over the last 18 months. I used Alexa to play songs from the ‘30s and ‘40s for her sometimes, which she really enjoyed hearing.

Although her recollection of our early childhood days seemed limited, there were many fascinating details about her life growing up in Arkansas that she told me about. Most of her childhood she lived with her mother and sister in the home of her grandparents along with many aunts, several of whom were close in age. Mother loved describing their lively dinner table and summer evenings relaxing on the porch while facing “the mountain” in Hot Springs.

My mother always regretted not attending college. Graduating high school at the height of the Depression, after her parents had divorced and her grandfather, who was a medical doctor, had died, she could not see how she could afford to go. Later she helped her sister financially attend school to become a nurse and Mother did attend some college classes in Marshall. She was very well read on many, many different topics. I asked her what she would have studied had she gone to college. Her answer was that she would have liked to be a political science or social studies teacher.

Since she was living with me and brought quite a few of her things, especially pictures and favorite books, now when I am at home I am reminded of her all the time. No matter their age, one misses the people you love so terribly when they die. But we were lucky to have had so many years with my mom. While far from perfect as none of us are, my mom was in some ways a model of strength. I learned from her how important it is to have faith in oneself and in the goodness of others and of life itself.

Polly Mann

Polly Mann

BY JOHNNY HAZARD

I met Polly Mann in the spring of 1977 when I was 18 and living in a little room by the tracks in the south Phillips neighborhood of Minneapolis. I had recently found out who she was because the Minneapolis Star had published a detailed profile of her and I was surprised that, having family in Marshall and being myself a budding pinko, I had never heard of her. I went to Marshall to see my grandmother and told her that I wanted to meet this woman who was in the paper. She said “Oh, you don’t want to meet her. She’s a radical.” I don’t remember if I ever told Polly this part, but I knew that right away she started to visit my grandmother, who stopped attacking her and spoke out when other people still did.

When my visit to Marshall was over, I hitchhiked back to Minneapolis. Less than an hour along, near Redwood Falls, a white-haired man in an Oldsmobile sedan stopped. He asked where I was coming from, where I was going, who I was visiting in Marshall. “My grandmother,” I said.

“Who’s your grandmother?”

When I told him her name he laughed.

“You know her?” I said.

“Yes, I know her.” And he explained why and who he was. I told him about the conversation with my grandmother about this man’s wife, Polly, and said that I wanted to meet her. He said: “Well. You see that car up ahead? She’s driving it. We don’t normally take two cars to the same place, but … So you can talk to her at the next rest stop.” We rolled along for almost an hour after that, and Walter trusted me well enough to say what he really thought of the FBI and the CIA – unusual for a sitting judge talking to a stranger. But he was that way. These were still the peak years of FBI attacks, via COINTELPRO, against the Black Panthers, the American Indian Movement, anti-war groups, and the legacy of Martin Luther King.

I rode the rest of the way with Polly and I visited her often in Marshall, St. Paul and Minneapolis for the next 40 years. In Marshall she showed me clippings of letters to the editors of the Marshall Independent which she usually signed, “Polly Mann, Marshall. Rural housewife.” She used the same bio when she spoke at public meetings. When she planned to leave Marshall, just before Walter retired, she said: “I’m tired of being in the news here every time I express an opinion. I feel that in the cities I will be just one more person working for causes.”

In those first years she showed me a short story she had written and I know that she kept working on it for the rest of her life because I always got the recycled paper and the type fonts were more modern every time. I think the title was “Princess Fay of the Freeway” and it was about an organization that put up memorials like the ones that we see for veterans every time that someone died for progress behind the wheel. She had said to me, “I’m not a light person,” but this was evidence of her satirical side.

I moved to Mexico in 2000, Walter died a few years later, and Polly moved from St. Paul to an elders’ apartment building in the Uptown area of Minneapolis. (The area had become a staging area for anti-militaristic protests thanks to WAMM, the Revolutionary Anarchist Bowling League and other organizations.)

In 2009, I went to her 90th birthday party. Someone asked that all of the people over 90 years old raise their hands – there were dozens. Within a couple of years after that party, she faced her first real health challenge, a broken hip. It was sad to see her limited to indoor activities in winter during those years, but I was glad to see that she was in good spirits and enjoying the phenomenon of physical therapy.

In 2018 and 2019 I saw her three times that I can recall. One time she invited me and her son Mike, still living in Minnesota, to eat at the dining place in the building. When she invited the second one of us she had forgotten about the first, but there we were. She beat us both viciously in Scrabble. It was around the same time that she said, “John, this may sound funny, but I’ve started writing a book.” She mentioned an author who had inspired her. I didn’t know who it was. When I got back home, I asked her a few times to send me the work so far by email. Before I received them, I said to Eddie Felien, “She’s writing a book. We have to get hold of it and make a commitment to finish it for her if necessary.” But when I started to read it, I found that I didn’t understand the concept well enough to do anything with it. It was more complicated than an autobiography would have been.

The last time I talked to Polly by phone was just after her 101st birthday in 2020. She is the only person for whom I was willing to participate in such an abomination as an online birthday party. I knew that she had COVID at the time but not everyone at the party did. She spoke very briefly at the party, paused, and then said, “That’s all.” I called her a few days later and could tell that she was not going to die. She said, “Come on over,” and I said, “You forget that I live in Mexico.” “Ah, that’s right,” she said. “Well, you know, the main problem with this COVID thing is that it’s really boring.” This was an unusually carefree comment, given that one of her close friends had just died of it and she herself had been at risk days a few days earlier. But I agreed with her attitude, as usual.

Polly, remembered

Polly, remembered

BY SARAH MARTIN

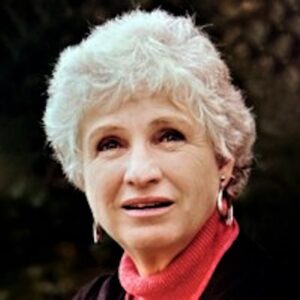

Polly Mann, a leading force and giant in the Twin Cities anti-war movement, died on Jan. 12 at the age of 103 in San Francisco, where she had lived with her daughter Connie for a little over a year.

In 1981, Polly called her friend, Marianne Hamilton, and said that we needed a peace group and the name should be WAMM (Women Against Military Madness). She knew that polls showed most women were anti-war, but they needed an organization to challenge the priorities of the current government’s spending priorities. Money for human needs, not the military and war. They were also concerned about the ongoing threat of nuclear warfare. They wanted a place for women to become leaders who would demand a peaceful and just society. Polly always thought big, made things happen, and remained involved. Until just six months before she died, she was still sending ideas and suggestions to the WAMM newsletter editor.

Polly began her lifelong commitment to peace and justice during World War II. She was a secretary at an Army base in Little Rock, Arkansas, during the war. Polly was appalled by how soldiers were being trained to kill, and deeply disturbed and saddened as she saw these young men go off to war. She knew then that she was opposed to war.

Polly’s fierce and relentless activism and opposition to all U.S. wars, interventions and occupations began with the Vietnam War. She was a field organizer in the Gene McCarthy campaign, and was present and tear-gassed on the streets during the police assault on protestors during the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968. During the Paris Peace Talks in 1971, Polly went with the Citizen Committee to End the War in Vietnam to observe talks between the North Vietnamese and the U.S.

She was the first volunteer staff person in the WAMM office. Nikki LaSorella, who was a co-director with Polly, said, “I would never have learned to trust my intuition and creativity if it wasn’t for her generosity and encouragement. I watched how she brought people into the organization by allowing them room to become leaders. Her fearlessness never faltered, even when she was challenged. Her love was always present and her belief in each member gave us all a place in this unique organization.”

Polly understood the importance of an office and staff to an organization and as a result she saw WAMM celebrate 40 years as a persistent anti-war presence opposing every U.S. war, intervention, occupation, sanction and coup during this time. At times these were unpopular positions such as WAMM’s early decision to support Palestinians in their struggle for liberation, opposition to the U.S./NATO dismemberment of Yugoslavia, and the U.S. involvement in the unsuccessful but destructive attempt at regime change in Syria.

Always well informed, Polly followed events closely and had a sharp and correct analysis and understanding of the depth and breadth of U.S. imperialism. She understood that capitalism was at the root of U.S. wars at home and abroad. Her response to the injustices, oppression and violence perpetrated on both individuals and countries in the crosshairs of U.S. militarism was swift and strong, and led her to immediate action.

Always well informed, Polly followed events closely and had a sharp and correct analysis and understanding of the depth and breadth of U.S. imperialism. She understood that capitalism was at the root of U.S. wars at home and abroad. Her response to the injustices, oppression and violence perpetrated on both individuals and countries in the crosshairs of U.S. militarism was swift and strong, and led her to immediate action.

She gave and organized material support to countless people. Sara Olson recalls, “Once, while incarcerated, I requested what is called an ‘Olson Review.’ My so-called ‘counselor,’ a former Los Angeles County sheriff, a former member of a corrupt bunch if there ever was one, had to wait while I read my entire C file (criminal file). I recall a letter Polly’s husband wrote to the California attorney general, telling him he should see to it that the judge on my case in Los Angeles be disbarred and why he, Walter, thought so. Next, there was Polly’s letter. As my counselor twisted and turned with frustration in his seat, I read her beautiful, well-turned phrases of support, tears streaming down my cheeks. While there are rarely good days in prison, for me, Polly’s letter made it one of the best.”

Lucia Wilkes-Smith remembers that, in 1985, seniors in the activity center on the Northside where she worked opposed the closing of the Social Security center near them. Budget cuts were supposedly the reason. This would force them to take care of their business at an office on the Southside, a bus ride with two transfers away. They decided to take action and called Polly to find out how to plan a protest. They were surprised and pleased when Polly came to their picket with her WAMM sign. Polly noticed the Army recruiting office across the street and said, in her distinctive Arkansas accent, “If they’re so worried about the budget, why don’t they shut that down instead of the Social Security office.”

One of WAMM and Polly’s first actions was to organize buses to the Seneca Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice to stop the scheduled deployment of Cruise and Pershing II missiles from the Seneca Army Depot to Europe.

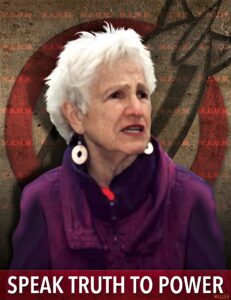

Polly went on delegations to many countries including Cuba, Libya, Central America and the Philippines to see and hear firsthand the effects of U.S. foreign policy. She ran a spirited campaign for the Senate in 1988 with the slogan “Speak Truth to Power.” She helped initiate an ongoing weekly vigil in St. Paul, Minnesota for Justice in Palestine, during the first intifada in 1988. She joined the picket line at the Hormel strike and, as Susan Giesen recounts, “Guardsmen were blocking the street. She marched right up to the line, approached each guardsman, touched him gently on the shoulder and said, ‘I know you don’t want to be sent to Central America. I will do all I can to not let them send you there.’”

An excellent and prolific writer, Polly wrote columns for the WAMM newsletter, Southside Pride and the Women’s Press for years, and also plays including “Victoria Reincarnated,” which was about Victoria Woodhull and her candidacy – even before women could vote – for the office of U.S. president. It was produced and directed by Ed Felien and starred Sara Jane Olson as Victoria. Polly was a popular speaker at innumerable programs and rallies, including at the Minnesota Capitol at the March on the RNC in 2008.

Polly was a beloved, respected and dynamic leader. Erica Bouza said in a WAMM newsletter devoted solely to Polly, “Greatness is rare. Not many of us have encountered it; the courage to stand up for what you believe and the skill to lead and persuade others to pursue the dreams of social, racial, economic and gender justice are isolated virtues, given to the very few. She is gutsy, scholarly, practical and effective, a devoted friend and an inspiration to those who dream of freedom, equality and justice.”

¡Polly Mann Presente!

Thank you, Polly

BY ED FELIEN

Many people get it wrong when they think about Polly Mann. They think of her as someone always protesting the government. Yes, she did that. She did a lot of that. But she wanted to change the government so much she took the next step. She imagined a government so much better than it was, that she wanted to be a part of it.

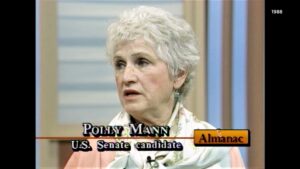

Her profound contribution to Minnesota politics was her run for the U.S. Senate in 1988. She ran for the DFL endorsement at the Rochester convention against Skip Humphrey. Humphrey was attorney general, the son of Hubert Humphrey. He believed it was his turn. The seat had his name on it.

Skip had much the same politics as his father. He was pro-war and pro-life. He had just prosecuted some gay guy in Stillwater for sodomy. I managed to ask him why he did that. He said, “It’s the law.”

Polly knew there were a lot of pro-peace and pro-women people in the DFL, and she wanted to reach them. Gay people worked hard on her campaign. They came to Rochester upfront and in-your-face.

My wife, Carol Hogard, and I worked the floor for Polly. We talked to delegates. After the first ballot, I went into the counting room as the official campaign observer. Polly got 40% of DFL delegates’ votes. 40% plus. That was enough to block the endorsement. Some people who had been left out for a long time, just got heard.

I ran out of the room back across the hall to our gang and shouted, “We did it. We blocked the endorsement.”

“No we didn’t,” they said. The chair had just announced that Skip won the endorsement by just over 60% of the votes. The Central Committee hadn’t voted yet. In the time it took me to leave the room after hearing the “final count” and running to my friends, the final count had been revised to include more than a dozen members of the DFL Central Committee.

We lost.

But Polly didn’t think we’d lost. She thought we’d won a great victory. She knew that a lot of people wanted to hear what she had to say. She broke from the DFL and ran for the U.S. Senate as a peace candidate. She got a little less than 5% of the vote. It was enough to cost Humphrey the race. He lost to David Durenberger.

The DFL was put on notice. Don’t send anyone to the Senate who isn’t pro-choice and pro-peace.

Two years later the DFL endorsed probably the most progressive man ever to run for the Senate, Paul Wellstone. My wife and I worked the floor. I organized a snake dance by delegates to drum up support. After the convention ended, people were streaming out of the hall. Jim Rice, the head of the Northside DFL machine, angry about the old guard being beaten by young radicals, screamed at me, “OK, now you can proclaim the Southside Soviet.”

I should have screamed back, “OK, but we’d have to call it The Polly Mann Southside Soviet.”

Thank you, Polly, for teaching all of us to have faith in the courage to change the world. It was a precious and beautiful gift. And what the world has learned from you it will repeat again tomorrow.