BY KAY SCHROVEN

BY KAY SCHROVEN

“The shoot first, think later approach to policing needs to stop.” – Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor

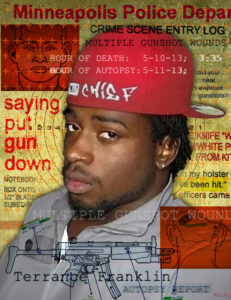

Before George Floyd, before Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and before body cameras were worn by the Minneapolis police, there was Terrance Franklin, aka Mookie. The case did not get a lot of attention in 2013. Now, after nearly a decade, the Walter Franklin family and their attorney, Mike Padden, are hopeful that Mookie’s case will get another chance at justice. The wrongful death settlement of $795,000 on Feb. 13, 2020, by the city of Minneapolis did not and does not settle it. Holding the officers responsible for Terrance Franklin’s beating and death would be a step toward justice. Former Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman announced at the time that “a grand jury declined to indict the officers because the case did not meet the standard of probable cause.” When the request to reopen the case was made because of new evidence, the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension (BCA) denied the request. Police wrongdoing simply was not taken seriously. However, by the time Freeman decided not to seek reelection last year, he seemed to understand that the case needed re-examination, but the timing was poor. He left his post on Jan. 3 of this year. Re-examination is a huge undertaking, and it made sense to leave it to his successor, Mary Moriarty. Will Moriarty reopen the case? Does the civil suit raise new questions about the culpability of the officers involved? “It’s not over,” says Padden.

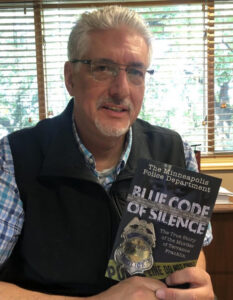

Terrance Franklin, a 22-year-old Black man, was killed by Minneapolis police officers. In his book, “Blue Code of Silence: The True Story of the Murder of Terrance Franklin,” Padden writes, “Peterson and Meath murdered Terrance, and the other three, Stender, Muro and Durand, helped them get away with it.” Mookie sustained nearly a dozen gunshots, including multiple shots to the head. He was suspected of a burglary, chased down and killed in the basement of 2717 Bryant Ave S., where he was hiding. Clearly, Mookie made poor choices; he ran and then broke into a home to hide. But did he deserve to die? The MPD did an internal investigation of its officers and cleared them soon after. Padden’s investigation suggests a different story.

What really happened on May 10, 2013, in that basement on Bryant Avenue? Why write about a case that is nearly a decade old? Answer: because money is not justice and sadly, Terrance Franklin’s story is not a unique or isolated one. In January, the city of St. Paul awarded $1.3 million to the family of Marcus Golden, who was shot and killed in 2015 by the city’s police. Amir Locke’s family recently filed a lawsuit in federal court against the city of Minneapolis for the 2022 no-knock warrant that turned deadly. And now the Tyre Nichols case is front and center in Memphis, Tennessee, where the five officers involved have been fired and charged with second-degree murder.

Michael Padden

In his book, author and attorney Mike Padden lays out in methodical and convincing detail numerous inconsistencies and contradictions in the case. One of the key pieces of evidence is an audiotape made by a neighbor living near 2717 Bryant Ave. S. Jimmy Gaines recorded the ordeal with his iPod Touch. Thorough examination of the tape with a formidable team, including work done by metadata experts and audio sound engineers, authenticated the Gaines tape, which tells a different story than that told by the officers involved. The Gaines tape became a taboo subject and was ignored by the defense until more than four months into litigation, a year and a half after Mookie’s death. Additional inconsistencies include no gunshot residue testing to see if Franklin’s DNA was on the gun, no blood on the MP5, no evidence of Mookie being armed, and no clarity on how two of the officers were wounded. Video images from the apartment building where the police tried to apprehend Mookie did not support the allegation made by an officer that “he tried to run me over.” Many questions remain.

Padden writes, “Technology changes everything. It is the great equalizer and is changing how citizens view the police.” If it weren’t for 17-year-old Darnella Frazier’s quick thinking, the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis may never have been captured on video and witnessed worldwide. While there is no such video of Mookie’s killing, there is the Gaines audiotape. This became a key piece of evidence for the prosecution because it picked up sound, voices and words, including police voices saying: “C’mon little n____, don’t go putting your hands up now.” And Franklin saying, “I am Mookie,” which flew in the face of the police narrative that “he never said a word.” You have to wonder, how many cases like this went down over the decades and remained unaddressed prior to today’s technology? Eight years after the Franklin case, three of the officers retained attorneys; two are seeking immunity with Hennepin County in exchange for new information.

In an effort to decrease excessive force, the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act of 2021 was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives by Rep. Karen Bass, D-Calif., and passed on March 3, 2021. The Act limits qualified immunity of officers as well as unnecessary force, no-knock warrants, chokeholds and carotid holds. The bill also seeks to create a national registry that would record complaints and misconduct of officers. In addition it directs the Department of Justice to create uniform accreditation standards for law enforcement agencies addressing racial profiling, implicit bias, and duty to intervene when another officer is using excessive force. The Act did not pass the evenly divided Senate amid opposition from Republicans. Negotiations collapsed in September of 2021. Is there a path forward? In his State of the Union address on Feb. 7, President Biden implied that there is, stressing the importance of holding law enforcement accountable.

Mookie’s case brought about changes – no more secretive grand juries. Police investigations became outsourced. It is said that the MPD (as well as policing in general) is not historically a culture of accountability. According to the Star Tribune, the city of Minneapolis paid $14 million between 2006 and 2012 due to MPD conduct, and $70 million over two decades. The newspaper further reported that of 95 alleged victims, eight involved officers were disciplined. In the 12 largest settlements there were no officers disciplined. At the time of Mookie’s death, Officer Lucas Peterson alone had 13 complaints against him for use of excessive force; Officer Michael Meath had six. The new city office designed to handle police misconduct had a total of 439 cases, but not one cop was disciplined by it.

The Franklin case remains relevant. While many police officers perform appropriately in the spirit of service, deserving of our support and respect, police brutality is sadly not a thing of the past. The blue code of silence might be defined like this: some police officers openly engage in unethical, immoral, and even illegal behavior, but they are often protected by what is known as the blue wall of silence – an unofficial agreement among law enforcement not to challenge each other’s misconduct. In order to understand it we must look beyond race, color and culture. And sometimes the code of silence can be more than just silence. It can include cover- ups. Padden offers an explanation, describing it as a system: “Once in it you must play by the rules regardless of who you are and where you come from.”

Shaun Harper, provost professor at the University of Southern California, says, “It is a cultural and institutional issue, ridden with systemic racism and anti-Blackness.” He goes on to describe how slave catchers were the original law enforcement officers and how policing is steeped in decades of anti-Black policies and tactics. “Racism is deeply embedded into its DNA,” asserts Harper.

Nationally recognized trial lawyer for justice, Ben Crump, writes, “Policy means nothing if you have a culture that is rotten, the culture has to respect the policy.” He explains how the culture, like most cultures, is handed down from generation to generation and doesn’t care what your background is, including race. Many become unintentionally complicit. It seems some individual cops are able to resist the hyper-masculine culture that allows for cursing, insulting, beating and sometimes killing citizens, but they are a minority. We need more of them. Training can help, but it alone cannot undo centuries of racism. Massive institutional change is needed. Without it, the abolitionists (the Defund the Police movement) are apt to grow in numbers.

Harper sums it up like this: “I care less about which of us has the right philosophical position on this – I just want police officers to stop killing Black people.”