BY CLINT COMBS

“I will invoke the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to target and dismantle every migrant criminal network operating on American soil,” President Donald Trump said at his campaign rally last fall. The Alien Enemies Act, a zombie law that dates back to the late 18th century and was last used during World War II.

Trump escalated his rhetoric by labeling Tren de Aragua as a “terrorist” organization, claiming the group’s alleged ties to Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro’s regime. The White House, in its justification, argued that Maduro’s government had enabled the gang’s illegal activities. A White House statement asserted that the regime “coordinates with and relies on TdA and other organizations to carry out its objective of using illegal narcotics as a weapon to ‘flood’ the United States.”

The Alien Enemies Act Paved the Way for Japanese American Incarceration.

However, the president’s assertion was quickly challenged. The New York Times, through investigative reporting by Charlie Savage and Julian E. Barnes, uncovered that Trump’s claims were not supported by the available intelligence. The NYT reported that U.S. intelligence agencies found no evidence that Tren de Aragua was acting at the direction of the Venezuelan government. In fact, officials concluded there were incidents in which Venezuelan security forces exchanged gunfire with gang members. One official, summarizing the findings, noted “The gang was not acting at the direction of the Maduro administration, and the two are instead hostile to each other.” Moreover, the gang was described as lacking the resources and centralized command needed to function as a tool for the government. The intelligence community found that although some Venezuelan officials were allegedly corrupt and had ties to gang members, this was not sufficient to classify the gang as an extension of the government.

These revelations prompted the Department of Justice (DOJ) to launch an investigation into the leaks of classified information surrounding Tren de Aragua. The DOJ, defending the president’s stance, argued that the Alien Enemies Proclamation was rooted in facts and legal precedent. They vowed to pursue legal action against anyone attempting to undermine the president’s efforts to expel what they deemed “terrorists” from the country.

The situation harkened back to a troubling chapter in U.S. history when the Alien Enemies Act was used to detain and deport Japanese, German, and Italian Americans during World War II. The law, passed in 1798, allowed for the detention of foreign nationals from nations at war with the U.S., without due process or oversight. Despite its history of abuse, the law remained on the books, largely dormant, for over 200 years.

This relic law resurfaced in the modern context of national security concerns. But as activists and descendants of those detained during WWII pointed out, its application today could have the same damaging consequences. Russell Endo, whose grandfather was detained during the war, expressed concerns about the broad power the Alien Enemies Act grants the president. He pointed out, “The problem with the Alien Enemies Act in World War II, and it still exists today, is that it doesn’t contain any provisions for oversight… so this gives too much power to the President.” His family, like many others, suffered due to the lack of due process. “My grandfather was a fisherman. He lost his fishing boat… he lost his business assets,” Endo recalled. He warned that this law could easily be misused against any group, noting, “It’s not going to just stop with gang members from Venezuela… it’s going to try to figure out how it can use the law against other people who are here, who are not citizens.”

Lauren Ebel, whose father fled Nazi Germany to avoid being drafted into the Hitler Youth, found herself reflecting on the historical parallels when her family’s past was revisited. Her father had “a revulsion against the Hitler Youth and didn’t want to be involved with it. He got into a fight and, in 1937, was sent to the U.S. He came to this country for freedom and loved it. But he felt betrayed when they didn’t recognize his patriotism.” Despite his efforts to escape the Nazi regime, Ebel’s father found himself caught in a legal and social system that treated him as a suspect purely based on his nationality. As Ebel explained, “The FBI came into my father’s home in the middle of the night, arrested him at gunpoint, and took him away.” He was sent to various detention centers, including Ellis Island and Fort Meade, Maryland: “There were no hearings, no witnesses, no due process.” This stark violation of his rights was a direct result of his nationality, as he was viewed as a suspect simply because of where he was born. Ebel’s father, who had sought refuge from Nazi persecution, was caught in a system that presumed his guilt because of his German heritage, much like the very regime he had fled.

Conrad Caspari, whose family was also directly impacted by the Alien Enemies Act, described a particularly absurd incident involving his father. He recounted how his father, who had been detained under the Act, was embroiled in a strange and ironic situation. A man in the family was accused of espionage simply because he played a mouth organ — a small instrument with a reflective tin part. The reflection of the tin was mistakenly interpreted as signaling messages to agents. As Caspari humorously noted, “It’s not really funny, but it is funny.” The charges, which Caspari described as “trumped up,” were ultimately dropped, and the man was acquitted. However, the hysteria surrounding the case did not end there.

The climate of fear and suspicion led the American Legion to label all Germans as potential Nazis, despite the fact that many, like Caspari’s father, had fled Nazi Germany to escape the very regime that was being falsely attributed to them. Caspari explained, “My father was strongly opposed to what was going on there, and he left Germany because of that.” Despite his father’s opposition to the Nazi regime, he was later re-arrested in 1942, along with others of German descent, and sent to a detention camp in Southern California. At the camp, over 2,000 detainees — Germans, Italians, and Japanese — were held without due process. Caspari’s father, a teacher, lost his job and was forced to leave California. As Caspari pointed out, “There was absolutely no due process; they were all assumed to be guilty, really, without having committed any crimes.” Caspari’s father, who had sought refuge in the United States to escape Nazi persecution, found himself being treated as a suspect based solely on his nationality, a situation that mirrored the unjust treatment of those he had tried to escape in Germany.

Katherine Yon Ebright, a legal expert at the Brennan Center, also raised concerns about the current application of the Alien Enemies Act. She pointed out the lack of any “evidentiary threshold” in the law. “If Pam Bondi wanted to look at a Venezuelan and say, ‘I deem her to be a member of Tren de Aragua with absolutely no evidence,’ there is no way to contest that decision,” Ebright argued, emphasizing how the law’s vagueness and lack of due process protections could lead to grave injustices.

This is not just a legal issue; it’s a deeply personal one for many families who were directly affected by the overreach of the Alien Enemies Act during WWII. The law’s original purpose — to protect the U.S. during a time of global conflict — has now become a tool of political power, used to label individuals based on their nationality and potentially target them without due process.

The broader concern, as Ebright noted, is that “bad reporting, credulous reporting” could lead the public to believe that the law is only being used to target gang members. In reality, its invocation could easily extend beyond its original scope, sweeping up innocent individuals based on their national origin. As she warned, “It’s all too possible that if there is an invocation of the Alien Enemies Act, it says we’re using this to target those deemed to be members of Tren de Aragua, but it’s not just about gang members.”

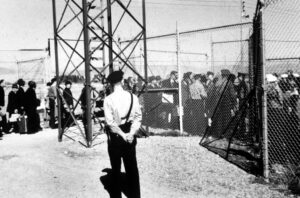

Alleged members of the Venezuelan criminal organization Tren de Aragua deported from the U.S. arrive in Tecoluca, El Salvador.

As the Trump administration and the DOJ continue to push forward with plans to invoke the Alien Enemies Act, the debate over its application will only intensify. The law, as it stands, represents a chilling reminder of the dangers of unchecked presidential power, one that has the potential to tear apart the lives of innocent people based on little more than their birthplaces. For many, the question remains: will we allow history to repeat itself, or will we reject this outdated, dangerous law once and for all?

Heidi Gurcke Donald shared a similarly harrowing account, which sheds light on the broader impact of these policies on German families, particularly in Latin America. “Well, my father was German, my mother was an American citizen, but we lived in Costa Rica,” Donald explained. “There was, if the Alien Enemies Act was not in play in Latin America, it was a completely different program called War Problems… The special war problems division was surreptitious. It was illegal. It was not passed through Congress.” Donald’s family was caught in this system, and her father, a businessman who had imported goods between Europe and Latin America, was arrested by the FBI, even though the accusations were never fully explained. Donald’s family was subsequently deported to the United States, where they were detained under the Alien Enemies Act.

She added, “My very strong reaction is, how do you know who these people are unless you give them a day in court?” Like Caspari, Donald’s father was denied due process. “My father did not have a day in court, and for a year and a half… During that time, he lost his business, he lost the country that he loved.” The family was eventually sent to the Crystal City Internment Camp in Texas, where Donald recalls being one of the many families impacted by this sweeping policy. She also described the human toll: “My father had been in prison. So that’s my father, Werner… He learned to be a chain smoker and died of it.” The trauma from this experience would have lasting effects on her family, both physically and emotionally.

Donald also recounted how the women and children of detainees were subjected to harsh conditions, left in limbo without their breadwinners. “The women and children were causing anti-American sentiment by being upset because they no longer had a breadwinner,” she explained. “They were creating enough of a fuss that the United States should take them too, so there’d be nobody behind to create any anti-American sentiment.”

This pattern of arbitrary detention and suspicion led to similar stories across the United States and Latin America, as families were torn apart, livelihoods were destroyed, and the principles of due process were ignored. For many like Heidi Gurcke Donald and Conrad Caspari, the long-lasting emotional and physical scars of these wartime policies are a painful reminder of how fear can lead to unjust treatment of innocent people based solely on their nationality.