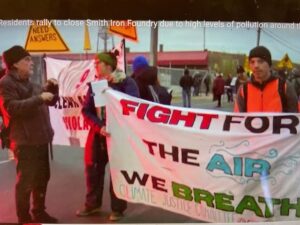

Demonstration outside Smith Foundry protesting pollution on

Nov. 10

BY DANIEL COLTEN SCHMIDT

Smith Foundry is an iron foundry in the residential East Phillips neighborhood. It has been in operation since 1923 and has been polluting the neighborhood since its inception. This past August, 100 years after the foundry opened, the EPA sent Smith Foundry a Notice of Violation under Section 113(a) of the Clean Air Act. The letter lists numerous violations of the Act, including emission of hazardous pollutants at roughly twice the Minnesota allowable limit, a zero-pressure reading on one of the foundry’s filters, a failure to maintain records of pollution control equipment inspections, and a failure to notify the MPCA about equipment failures. The letter states that Smith Foundry is liable for judicial civil or criminal action.

And yet, to the horror of the community, for the past three months since the issuance of the Notice of Violation, the foundry has continued to operate its business as usual. Every day, South Minneapolis residents step outside to the smell of fumes, and we know without a doubt that they are toxic. And in spite of the nation’s highest environmental law enforcement office – the EPA – citing the foundry with breaking the law, the polluters continue to rake in profits at the expense of Minneapolis residents’ health.

On Nov. 27, the East Phillips Improvement Coalition (EPIC) hosted a meeting between the MPCA, EPA, and the community. Approximately 100 community members were in attendance. Nikolas Winter-Simat, executive director of EPIC, asked the community members in the room, “Who in the last few months has not gone outside because of the smell, not allowed their kids to go on the Greenway, not allowed their kids out, had to close their windows – any of those things, because of the toxic smell?” A vast majority of those in the room raised their hands.

A mother who sends her son to the Circulo de los Amigos child care center across the street from Smith Foundry said, “My son started going there earlier this year– and he never had any significant health problems or breathing problems – but shortly after, he got sick and had trouble breathing and ended up in the emergency room. … We had to get him tested for asthma, which he does have now. And I feel guilty for not knowing what I was exposing him to. But I shouldn’t have to feel like that. I should be able to trust that my community is safe for my son.”

Many community members expressed the feeling that the regulatory agencies were not answering their questions directly and were not listening to the stated needs of the community. Luke Gannon, director of program engagement with EPIC, in a conversation after the Nov. 27 event, said, “I don’t think I learned anything new. You could tell they were scripted.” Nazir Khan, a community organizer with the Zero Burn Coalition (formed around the campaign to shut down the HERC incinerator in North Minneapolis) said to the MPCA representatives present, “You’re not hearing what people are saying. You have to shut this facility down. Period.”

Many community members expressed the feeling that the regulatory agencies were not answering their questions directly and were not listening to the stated needs of the community. Luke Gannon, director of program engagement with EPIC, in a conversation after the Nov. 27 event, said, “I don’t think I learned anything new. You could tell they were scripted.” Nazir Khan, a community organizer with the Zero Burn Coalition (formed around the campaign to shut down the HERC incinerator in North Minneapolis) said to the MPCA representatives present, “You’re not hearing what people are saying. You have to shut this facility down. Period.”

The MPCA has been downright negligent for over 25 years since Smith Foundry’s air emission permit lapsed in 1997. They have been operating under a provisional permit ever since. At the Nov. 27 meeting, the MPCA was asked, “How long are they allowed a provisional permit? Is there a time limit on that?” Frank Kolasch, assistant commissioner of the MPCA, replied, “They are allowed to operate under their current permit until we issue them a – unless they make changes to their facility.” In fact, the MPCA has been working for over seven years to reissue this permit, which is supposed to expire every five years.

For 15 years the MPCA has avoided enforcing the Clark-Berglin cumulative impact law which states that any business or agency releasing air pollution within a half-mile radius of the “arsenic triangle” in Phillips neighborhood must do a “cumulative impact analysis” before they can receive a permit to operate, including a new or reissued permit. That means that the permit must take into consideration the already existing health burdens of residents who will be impacted by that pollution. In an area like East Phillips, where it is well documented that environmental health issues like asthma and cardiovascular disease are already disproportionately high, the permit must raise the threshold of protection and require a stricter air pollution permit.

I asked former state Rep. Karen Clark, chief House author of the 2008 cumulative impact bill, and resident of East Phillips, why the MPCA hasn’t enforced the cumulative impact law with Smith Foundry, and she replied: “When we ask the MPCA that question, they always respond, ‘We’re working on it!’ There’s always an excuse, year after year. At a certain point, the pace of bureaucracy can’t keep being the reason. We have to ask, ‘What are the powers that are interfering with this enforcement at the MPCA?’”

Evan Mulholland, director of the Healthy Communities Program at the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy (MCEA), in a recent interview said, “This foundry has been emitting pollutants that are toxic and have been contributing to public health harm for its entire operation. That’s the problem of cumulative impacts: when you have people living in a place where particulate matter (PM) is elevated because of highways, and construction, and Bituminous Roadways, and truck traffic, and emitting metallic particulates into the air, in a way it doesn’t matter if there is a permit violation or not, the emissions are contributing to the cumulative impacts.”

The original intent of the 2008 Clark-Berglin law, according to Clark, was to reduce “excess burden on our community” as it relates to the social determinants of health – race, income, occupation, language, and location, among other factors. Using the results of a public health survey taken in the East Phillips neighborhood, along with data collected from the Minnesota Department of Health, the Minneapolis Health Department, the Minnesota Hospital Association, and the MPCA, Clark worked with the legislative GIS office to create a visual map showing how these social determinants of health played out in the real world. After decades of grassroots efforts, the community’s knowledge was finally validated that the overwhelming health disparities in their neighborhood are real.

Mulholland, who once served in the New Hampshire Attorney General’s office, described how environmental law can responsibly be enforced: “If there is an ongoing violation that has not been fixed and is harming people, then you have to think that one of the steps … is to shut down the facility until the risk to public health is stopped.” While Mulholland recognizes that there is not yet enough publicly available data to determine exactly what should happen, he is clear in saying that “as far as I can see, no one has ever tested or measured the amount of lead, heavy metals, and other hazardous pollutants coming out of the stack.” (The stack is the chimney above the furnace where they melt the metal.) Further, not only is there no data, but there is no filter in the stack at all. The emissions are entirely uncontrolled.

Why, after the EPA has cited Smith Foundry for violating the Clean Air Act, does Smith continue to operate? Why are environmental criminals allowed to negotiate behind closed doors with enforcement agencies rather than face the same punishment as petty criminals? Why does my family and my community have to endure trauma every day knowing that the foul smell in the air is exposing us to a greater potential for premature death?

Even in Minnesota, one of the progressive bastions of the country, environmental law enforcement is proving incapable of protecting people from pollution. We are far too deep in this colonial environmental crisis to continue to prioritize profits over people. As community member Andrew Falstrom said at the Nov. 27 meeting, “There is no repair for stolen lives.”