BY ED FELIEN

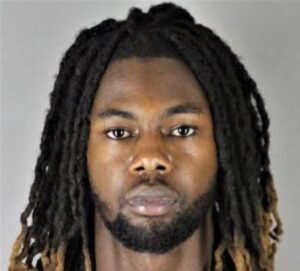

Jawan Carroll

Jawan Carroll has been charged with two counts of second-degree murder resulting from the shootout in front of the Monarch nightclub at 2 a.m. on May 22. He allegedly was with two other people. He had been identified by police authorities as a member of the Tre Tre Crips Gang. The Tre Tres seem to like to travel in groups of three. According to video taken at the scene, one member punched Christopher Jones and Carroll pulled out a gun and started shooting at Jones. Jones pulled a gun and began firing at Carroll. In the exchange, eight innocent civilians were wounded and one innocent civilian, Charlie Johnson—who was set to graduate from St. Thomas the next day—and Christopher Jones were killed.

Violent crime is up in Minneapolis. There have been 32 homicides already this year. More than 190 people have been killed or wounded in shootings this year compared to 75 at this point last year. In 2020 violent crime increased by 21%. In ranking cities for violent crime and crimes against property, Minneapolis ranked worse than Chicago and was almost twice as violent as New York and Los Angeles.

What’s happening?

Why?

Let’s get some historical perspective.

After Prohibition took effect in 1920 the national homicide rate rose 78%. There was a 24% increase in the crime rate between 1920 and 1921. The Spanish Flu from 1918 to 1920 infected 500 million people and killed 50 million worldwide. Alcohol was known to aggravate symptoms of the flu, so a well-meaning Minnesota congressman, Andrew Volstead, earnestly trying to make America healthier, authored the Volstead Act prohibiting the sale and manufacturing of alcohol.

A hundred years later, nine well-meaning Minneapolis City Council members proclaimed the Powderhorn Manifesto and their intention to defund the police. This seemed a natural and reasonable act in the wake of the murder of George Floyd by Officer Derek Chauvin to curb the racist murder of young Black men by the police. Of course, national street gangs that distributed heroin considered this an engraved invitation to battle for turf in this new liberated landscape in much the same way Sicilian gangs (the Mafia) considered Prohibition an invitation and battled other marginalized ethnic groups for turf in the distribution of illegal liquor during Prohibition.

Both good-intentioned Minnesota initiatives paved the road to hell for the rest of the country. Prohibition gave the Mafia a permanent place of prominence in liquor, prostitution, the longshoremen’s union and the construction trades. The Powderhorn Manifesto in South Minneapolis gave Republicans a hot button issue they used in the 2020 election to take back 13 seats in the House, win close races in the Senate and almost win the presidency.

The business plan for dealing heroin in North Minneapolis has been very successful for the Tre Tre Crips. A kilo of heroin costs about $30,000. That’s a thousand grams. A gram of heroin sells for $5 to $20. How can you make any profit if your cost is $30 a gram and you’re selling it for $5? Generally, a dealer will cut heroin 10-to-1, so one kilo becomes ten kilos. So, even if they sell it for $5 a gram, that’s a 40% markup. But, if it’s been cut only once, it should be worth $20 a gram. Quite often heroin on the street has been cut twice: one kilo into ten and ten kilos into a hundred. The danger of an overdose from heroin generally occurs when someone who is used to a 100-to-1 dose gets one that is 10-to-1 or pure heroin straight from the original brick.

In theory, dealing heroin can be extremely profitable. A $30,000 investment can return $100,000 if you are cutting the heroin 10-to-1 and selling it for $10 a gram. If you cut the original brick 100-to-1 then you’re looking at a potential return of a million dollars. Of course, that almost never happens. A lot of the heroin gets used up as samples and dealer tastings. But the allure of quick profits seems irresistible to young men who see few other options for economic advancement.

Of course, there are hazards on the path to easy riches. The legal penalties for the sale or distribution of heroin are two to 20 years in prison depending on prior convictions. But the greatest hazard is the competition. In competition with the Tre Tre Crips in North Minneapolis are the Bloods, the Stick Up Boys, the 1-9 Block Dipset Gang and others. The deadly shootout in front of the Monarch at closing time on Saturday night was probably a battle for turf and the chance to reach customers for heroin leaving the nightclub still looking for fun.

How do we stop the violence?

We could eliminate the problem immediately if we made heroin legal and easily available. The dosage would be standard, so there would be no chance of an accidental overdose. Eliminating the illegal street market for heroin would eliminate the gang-war competition for turf.

This would eliminate the most attractive avenue for violence at this time, but it wouldn’t eliminate the violent competition among young men. Boys are taught at a very early age, informally through examples and through the glamour of movies, that life is a competitive struggle. Someone else is trying to take something away from you. There’s only enough to go around, and you’re going to have to fight for your piece of the pie. That’s the American way. But that’s not how the rest of the world operates. In almost every other industrialized nation there is a generous social welfare safety net that protects you from cries of anguish and desperation: free medical care; free college or trade school education; guarantees of a living wage; subsidized housing; etc. These are national issues and, thankfully, Bernie, AOC and Ilhan Omar are working on them. But what can we do locally to stop the violence?

The first step, it seems, is to recognize we have a problem. We need our schools to counteract the violent and aggressively competitive propaganda our children are being taught on TV and on the street. Children need to be educated on how the economic system works. They need to see how they could fit in, how they could be productive and enjoy a happy and peaceful life.

The city and county public health departments need to organize block clubs in troubled areas of the city. They need to pay block club organizers to be nosy aunts and uncles, talking to their neighbors: finding out if they have enough food; putting them in touch with food shelves, food stamps and commodities; telling them about day care and educational opportunities for their kids; finding them jobs; helping them fix their homes; etc.

We cannot hide our heads in the sand and pretend the problem will go away. It will go away only if we confront it with our eyes open.

It was a tragedy that eight innocent victims were wounded and perhaps permanently scarred. It was a tragedy that Christopher Jones was killed, and it was a tragedy that Charlie Johnson never got to graduate from St. Thomas. But it is also a tragedy that Jawan Carroll saw no other options. His life is also over. Done. Wasted. And we are all the poorer for that.