BY ELAINE KLAASSEN

Michael W. Quinn

Remember a few years back when Twin Cities Nonviolent partnered with individuals and peace organizations to create 10 Days Free from Violence in the Twin Cities? It was in the fall. The initiative wasn’t so huge the first year, but the next year, in 2019, hundreds of peace organizations were involved and there was a roster of hundreds of peace events you could attend.

I went to one of them at the Minnesota Church Center on Franklin Avenue. The 90-year-old well-known activist priest Father Harry J. Bury was there sharing inspiring words. There was also a young Black man who worked with gang kids in the streets in North Minneapolis who had challenged “his kids” to spend 10 days without violence. The kids were excited and hopeful about it, he said. They put their souls into it. Wouldn’t you, if it was a choice between life and death? Those kids don’t want to die.

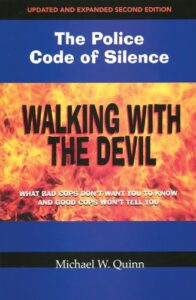

Also present was a retired Minneapolis police officer, Michael W. Quinn, who told me he had written a book about de-escalation and the code of silence in policing, “Walking With the Devil: What Bad Cops Don’t Want You to Know and What Good Cops Won’t Tell You.” (I later learned he was an international ethics and leadership trainer who had led a 2018 workshop – at 10 Days Free from Violence – on active bystander and peer intervention training to de-escalate violence.)

The book, written originally in 2005 and revised since then, says on the cover it’s the third edition already and gives two phrases that describe what the book is about: “The Promise of Peer Intervention” and “The Police Code of Silence,” followed by the title. It’s an important book that I believe too few people have heard of. It’s been lauded in the field but apparently has yet to make an impact on the Minneapolis Police Department. Needless to say, Bob Kroll is not a fan of Mike Quinn.

It seems that back in 2005 the lack of accountability we are especially concerned with now was addressed thoroughly. Except who was listening? Who read the book and heeded its counsel? It’s all in there.

Quinn was invited to help create a peer intervention program in the New Orleans Police Department, EPIC (Ethical Policing is Courageous), which is operating today. It’s more than a shame the MPD didn’t invite him to do the same here. If police officers, even rookies, would have had permission and support for intervening in fellow officers’ bad behavior, George Floyd would still be alive.

I believe that in general a lot can be forgiven and overlooked in “tense, uncertain, and rapidly evolving” situations, as police situations are characterized many, many times in the book. But May 25, 2020, wasn’t an example of a “tense, uncertain, and rapidly evolving” situation. That is no explanation, or excuse, for the tragedy.

In my opinion, a belief embedded in everyone in this culture took over in the actions of Derek Chauvin that day at 38th and Chicago: the belief that Black and Brown people are bad, inferior and of no importance. Yet, the rule of law doesn’t support that belief. And the rule of law is what the law requires police officers to follow. So, if Minneapolis police culture had had in place the permission and support for all officers to monitor the behavior of other officers, the outcome would have been different. Of course, it should never have come to the point that intervention was necessary, but it did. The current fear that officers have of the public, since officer assassinations have risen significantly in recent years, which Quinn writes about in the book, also escalated the brutality – and made peer intervention necessary.

Quinn’s vivid, often riveting, moments in “Walking with the Devil” describe the heights and depths of police work – the best, the worst and in between. He admits to their love of the adrenaline rush; he praises the selflessness that led them into the Twin Towers; he describes the blatant corruption (robberies and selling stolen merchandise) that goes on in the department; he admits to his own errors that he wishes he could undo.

Throughout the book he refers to the “no ratting” agreement within the police force as well as to the power of one person to make a difference. He gives numerous examples of times when one officer has spoken up, himself included; although the whistleblowers pay a price, their courage nevertheless makes a difference in modifying bad behavior within the ranks.

For the average citizen, the book will take you into an unfamiliar world, a world full of wrongdoing and harm-doing. Quinn presents convincing scenarios that describe inexplicable behavior by “the scum of the earth.” Within the ethos of the police force it appears that those citizens who commit crimes (act outside the law) are seen as not quite human. He shows the impulse of police officers to get every situation under control. It’s a rough world.

There are many gray areas that police officers run into, which Quinn describes vividly and in a way that wins our sympathy. Quinn also draws us into his exciting storytelling of scenarios unfamiliar to ordinary citizens so we can understand situations that are so violent, so life-threatening, so crazy and unexpected that the officers involved really can’t remember exactly what happened.

You can start to grasp how it is possible that officers will cross the line.

Two important passages dramatize why officers need to maintain impeccable ethics: “[W]hen we hurt people unnecessarily or make them lose face in front of others, just because we can, we are making a serious mistake. … Many of these citizens have nothing and they know it. Being on the bottom of the pile economically and socially drives them to fashion an inversely high sense of honor. When we take that away from them with physical force or words of disrespect, we take away the only thing they have left. We create an enemy who has nothing left to lose, except his life or yours.”

Quinn cites the example of Lt.-Gen. Ian Freeland in Northern Ireland who thought it didn’t matter what the people of Northern Ireland thought of him and his troops. Quinn says it matters how people in authority behave. They have no right to enforce the law when they’ve lost their legitimacy. Quinn writes, “Instead of dealing with the cause of our loss of legitimacy we militarized our police departments in a failed attempt to change and control the bad outcomes of poor policies, much as Freeland did.”

Most people have internal controls and don’t need the external controls provided by legitimate law enforcement. Internal controls include a sense of right and wrong, a connection to the common good, a conscience, hopes and dreams, self-affirmation. Internal controls are developed in people whose needs are met: food, shelter, belonging, kindly companionship, respect, education.

When police officers don’t have their own internal controls, they need something external, like maybe liability insurance. As it is, there are forces in place that take away the deterrents to bad behavior, such as unions. I read in Mother Jones, September/October 2020, that with the formation of police unions, between 1950 and 1980, there was a noticeable increase in police killings in the U.S., “an increase that researchers say may be linked to officers’ belief that their unions would protect them from prosecution.”

My one big question about the book is this: Quinn talks about how many officers are prosecuted and do jail time for their brutality and other misbehavior. He talks about peer intervention as the way to prevent their career loss, incarceration, separation from family, etc., but my perception, and I think the general public’s perception, is that the police “always get away with it,” so I was surprised to read that many police officers are convicted of misconduct. I couldn’t get ahold of Quinn to ask him about this.

The book is available online from eBay and various booksellers. You can also order it from your favorite local bookstore. And don’t forget the library. The Hennepin County library system has an eBook available, but its two hard copies are in use, with 28 holds. So get in line. This is the book we needed in 2005. We still need it.