BY JOHNNY HAZARD

The recent history of immigration through Mexico to the United States is one of “Meet the new boss, same as the old boss,” of the realization that the arrival of liberal or moderate presidents in both countries has not led to an examination or reversal of the draconian policies of their reactionary predecessors. The response of both governments to the immigrant caravans that have moved through Central America and Mexico since 2016 is an example of this.

Some of the caravans have been organized partly by former Minnesota resident Irineo Mújica, who was born in Mexico, moved to the U.S. when he was 13, and now lives in the border state of Sonora. He returned in 2013 to Mexico because he was moved by what he saw of the plight of Central Americans in Mexico. His intention was to stay for a while and take pictures, but he became deeply and permanently involved.

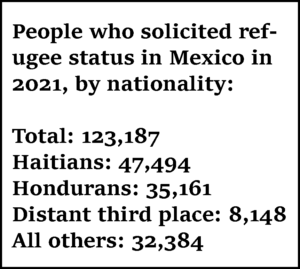

Immigrants currently in Mexico (often with the intention of arriving to the U.S.) are mostly Hondurans and Haitians, with significant numbers from El Salvador and Guatemala and several African countries. Others are from Nicaragua, Belize, Cuba, Venezuela, and the ex-Soviet bloc countries. Most Central American countries have large Black populations, especially on the Atlantic Coast. Here is the website of the largest Afro-Honduran organization: http://ofraneh.org/ofraneh/index.html.

Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) took office in December of 2018 after having campaigned for 14 years and having lost two elections due to the fraudulent behavior of the then-dominant parties PAN (Partido de Acción Nacional) and PRI (Partido de la Revolución Institucional). The seeds for repression against immigrants were planted when Felipe Calderón, president under the banner of the PAN from 2006 to 2012, immediately launched a “war on drugs” (taking a brilliant idea from Nixon and Reagan and not bothering to change the name).

Calderón’s successor, Enrique Peña Nieto of the PRI, continued this policy, which López Obrador opposed until he became president. AMLO, parting from a historical fallacy about the nature of the army, has given to the military the tasks of airport construction, customs, security at mass vaccination sites, and other civilian activities. Uniformed military leaders appear on the podium with him at events all over the country. One aspect of AMLO’s militarization is the creation of a national guard with army commanders and almost unlimited powers and responsibilities, including immigration enforcement. When it became impossible to deny accusations that the immigration police were incompetent or violent, the National Guard came to the rescue but has not refrained from tear-gassing pregnant women, arresting mothers and separating them from their babies, shooting people “accidentally” and other egregious acts.

In the summer of 2016, when Peña Nieto was still president, the first public caravans formed and advanced rapidly through Mexico with the support of the left and some church and citizen groups. People in the towns they passed through organized to provide food and shelter. Opposition came from a few outright xenophobes within Mexico and from a few U.S. political actors who thought the caravans were a plot to create a border crisis for Obama, Biden, and Hillary Clinton, and to support Trump (or vice versa, to oppose Trump), as if people who fled Honduras under desperate conditions were aware of the day-to-day vicissitudes of U.S. electoral politics.

As AMLO coopted progressive forces, support for immigrants diminished

Irineo Mújica, mentioned above, is founder of Pueblos Sin Fronteras. Late last year, the biggest of the recent caravans set out from Tapachula, Chiapas, with 4,000 migrants who pushed through a National Guard roadblock on the outskirts of the city and continued toward Oaxaca. Mújica said Tapachula, a city near the border with Guatemala, had become an open-air prison for migrants. This caravan advanced on foot over several weeks toward Mexico City and upon arrival was met by local police directed by Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum, a protégé of AMLO. The police attacked and tried to keep the people from entering the city. This time the people fought the law, and the law did not win: six cops were injured. The caravanners rejected government shelter, ended up in a casa del migrante and after 10 days, on Dec. 22, extracted a promise from the federal government to issue humanitarian visas and to discontinue the bizarre policy of detaining immigrants in Tapachula and dropping them by the hundreds in cities like Acapulco and Monterrey. (This waffling in policy is typical: one week the government says it’s urgent to keep people in Tapachula; the next, to disperse them.) Of the 510 people, 57 Haitians elected to remain in Mexico City, 100 chose to seek permanent residence in Mexico, and the rest got (voluntary) bus rides to the northern cities of Monterrey, Juárez, Chihuahua or Hermosillo where the wait for a visa would be shorter and the border closer.

The U.S. role: Biden canceled some of the most notorious policies of his predecessor, such as the separation of children from their parents. But crowding in private prisons continues, as do mass deportations and the policy of forcing asylum seekers to wait in Mexico, all documented on the United We Dream site: https://unitedwedream.org/protect-immigrants-now/biden-stop-deportations-now/. The participation of the U.S. in exacerbating misery in Honduras is discussed in this article which was written too long ago to mention Trump’s intervention in the second-to-last presidential election: https://theconversation.com/how-us-policy-in-honduras-set-the-stage-for-todays-migration-65935.

Another Mexican city with a large migrant population, all the way across the country from Tapachula, is Tijuana. This is the city with the largest number of Haitians who have decided to remain in Mexico. A few have work permits and work at “real” jobs; others have informal activities like washing windshields, selling products on the street, etc. Unfortunately, 16 Haitians have been murdered in Tijuana since 2016 – the most recent case was on Jan. 1.

In other northern cities like Chihuahua, it is common to see Hondurans or Haitians in convenience stores after a day of asking for donations on the street, changing dozens or hundreds of coins for bills. My friend Aurora of the Rarámuri (Tarahumara) Indigenous group and now resident in the city of Chihuahua, says of Black immigrants: “Let them come here. We’re not racist.” Any stigma against panhandling should be mitigated by the fact that the Mexican minimum wage is about five dollars a day and even a job like that is hard to come by for a person without papers.