Dried cod arrives from Norway in time for Christmas.

BY STEPHANIE FOX

It’s nearly Christmas and here in the North, that means holiday lights, tinsel-covered trees, and lutefisk. For many, it isn’t Christmas without a traditional bite or two of this iconic Norwegian delicacy. What many people don’t realize is that most of the country’s lutefisk originates right here in Minneapolis. The 123-year-old family-run Olsen Fish Company is the largest producer of lutefisk in the western hemisphere (and maybe the world).

From September through May, Olsen’s crew works to turn hard, dry cod into ready-to-cook slabs of lutefisk using a recipe handed down from the Vikings. It was a way to preserve fish before the invention of artificial refrigeration. The cod is high-grade, line-caught off Norway’s Atlantic coast, then hung on racks to dry in the unrelenting costal winds under the almost-24-hour Arctic sun. From there, it’s shipped to Minneapolis.

Turning dry planks of fish into ready-to-cook lutefisk is an exacting process and many of the Olsen Company’s crew members are lutefisk professionals, said company president Chris Dorff. It’s a union shop and some workers have been there for decades. This is not easy work. It’s chilly on the factory floor and the smell of fish is everywhere, even in Dorff’s corporate office. During the busy season, Dorff says he puts in 60-hour weeks, with some of that time spent alongside workers on the factory floor.

Olsen Fish Company delivers lutefisk and pickled herring.

When the dried planks of fish arrive from Norway, they first need to be reconstituted by washing in fresh water over a period of 14 days, then again in cold water with food-grade sodium hydroxide (lye) made from wood ash for several more days. The process, says Dorff, is highly refined, with controlled air temperature and humidity.

Then, fresh water is added to take down the pH level and the lutefisk is hand packed, ready to ship to retail outlets mostly in Minnesota, Wisconsin, North and South Dakota, and northern Iowa.

“We also ship pallets to Arizona, Florida, Southern California and to some of the prairie provinces in Canada – any place in North America with Scandinavians,” said Dorff.

Dorff speculates that the reason so many people claim not to like lutefisk is that a lot of Midwesterners tend to overcook fish, and lutefisk is no exception.

Char Juntunen, who once ran the lutefisk fundraiser at the First Lutheran Church in Duluth and served more than 500 pounds of the fish each year, was adamant about preparing lutefisk. “The hard part is you have to watch it,” she said. Juntunen advised home cooks to preheat their ovens to 400 degrees, then put the lutefisk on a lightly greased, rimmed cookie sheet. “After about 10 minutes, I stick my fork in the pieces to test. When it feels like it’s going to flake, it’s done. If it looks like snot, don’t eat it.”

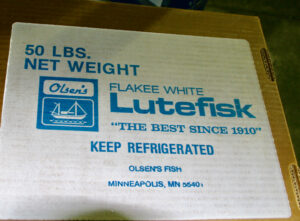

Boxing up the lutefisk for the holidays

Those folks who are put off by the presence of lye in lutefisk should know that the same lye is used to process green olives, masa harina (corn flour) used in making cornbread and tortillas, soft German pretzels and corn nuts, as well as many cocoas and chocolates.

The popularity of lutefisk was already falling before the pandemic, with sales dropping from five to eight percent every year, but the pandemic accelerated that decline. Pre-pandemic, the Olsen Company would sell 400,000 pounds of lutefisk during the holidays. Now, sales are half that. “It’s been slow getting back to normal,” Dorff said. “We lost churches and restaurants, and family celebrations weren’t happening. But this year it’s starting to come back.”

And prices for lutefisk have been going up, Dorff admits. “Prices have gone up more than 30% compared to before the pandemic. The cost of fish has gone up based on market price, as have wages set by the Norwegian government. And then there’s the cost of shipping from Norway. We buy the fish by the container and the price is the same whether you have a full container, a half container, or a third.”

While lutefisk is a regional food and sales are fading, pickled herring, also produced at the Olsen Company, is growing more popular.

One reason for herring’s popularity is the nutritional benefits. Herring is high in protein, an excellent source of B vitamins and zinc, and is low in saturated fat. And herring is loaded with omega-3s. “Only two ounces of pickled herring has 500 milligrams of omega-3 fatty acids,” says Dorff.

Olsen’s brand of jarred pickled herring, produced using an original recipe, with sugar, distilled vinegar, fresh sliced onions and spices, is the best-selling brand in the Midwest.

“But we sell it all over the country,” Dorff said. “Lutefisk is for people who have Scandinavian heritage. But the East Coast and New York, along with Florida, have some of the biggest herring markets in the country. It’s eaten by Eastern European Jews and Russians as well as Scandinavians. It’s been a big part of our growth. Our sales of herring have been growing every year.”

The Olsen Fish Company’s website has a special recipe for lutefisk leftovers – the Norwegian Lutefisk Taco. Top a piece of lefse with a thin layer of mashed potatoes. Top that with flaked lutefisk. Pour melted butter over the top. Add salt and pepper to taste. Happy holidays!