BY DEBRA KEEFER RAMAGE

Hmong family Tet in Vietnam

“You don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone,” Joni Mitchell famously sang. I have been thinking about the many local delights that are gone, or may be soon.

In 2016 I was still working for Heart of the Beast Theatre. We put on “La Natividad” that December. Two years later, after I retired and left, there was a one-off Winter Solstice show called “The Longest Night.” There was no show at all in December of 2019. This year, after a year without even the MayDay Parade, HOBT is on furlough for an indeterminate length of time. I hope I’m wrong, but it seems to be shrinking away.

Of course, this story is repeated many times, across the Twin Cities, across the Midwest, across the country and around the world. As we are being battered by climate chaos, poverty for many more induced by a yawning and growing chasm of wealth disparity, the almost inevitable growth of reckless extremists, including resurgent fascism, and then this year, the one-two punch of COVID-19 and its associated structural economic depression—cultural riches that were based on voluntarism and crowds (healthy people) and property values and philanthropy (wealthy people) are being starved out of existence.

St. Nicholas

We took these things for granted, and we should not have. Now that we have worked through the pain of surrendering them (if we have), along with restaurant dining, parties in bars, family get-togethers, Big Sports, and cautiously trusting our governments and corporations, we should probably ask ourselves: What things are we still taking for granted that will be snatched away from us next? The internet? The entertainment industry? The food distribution system? The power grid? Running water? The theoretical rule of law?

Refugees (‘Flight into Egypt’ by Botticelli)

In a way, the plagues of the past were not as terrifying as this one, even though they could and sometimes did fall to the rock bottom (the Black Death of mid-14th century Europe killed something between 30 and 60 percent of the population in just four years). Rock bottom is still the same place, but the heights we fall from are much greater.

At this point you’re probably asking yourself why on earth I started out an article titled “Holidays are Holy” with five paragraphs about pain and loss, culminating with the Black Death. The reason is I am leading up to a discussion of refreshment. Not refreshments, like cookies and cold drinks, but refreshing, reloading, starting over, hitting the reset button.

Consider the Black Death, for example. That was a horrible calamity, probably beyond our ability to comprehend. But for the survivors, it was the dawn of a new era. With the population so drastically reduced, it became a time when the rich could only get labor from the poor by giving them wages of real value. The peasantry, who had previously been little more than slaves, began to build modest wealth. This led first to the decline of the feudal system, and ultimately to the so-called Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution in the next three centuries.

This is illustrative of a sweeping historical phenomenon documented by Walter Scheidel in his book “The Great Leveler.” His inescapably argued hypothesis (at least inescapable if you don’t go back before about 800 B.C.E.—more on that in the next paragraph) is that wealth inequality always rises in the context of a civilization at its breaking point, and it is only reversed by violence, which he divides into four broad outcomes: war (example: WWI), revolution or civil war (example: the fall of Rome), environmental catastrophe (example: the destruction of the Mayans), and plague (example: The Black Death).

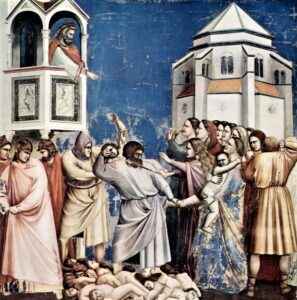

‘The Slaughter of the Innocents’ by Giotto

To lead into the subject of reset buttons, and 800 B.C.E., we need to look at a later, and not as popular, book: Michael Hudson’s “…and forgive them their debts.” The hypothesis this book sets out is that in the ancient civilizations that preceded the democracy of Athens, the wise men and rulers understood something that those great “civilization founders” of Greece and Rome denied or forgot: that wealth inequality, once it starts, will grow inexorably to the point of collapse, and all will come to a violent end, unless you hit the reset button.

Now, these civilizations were ruled by godlike tyrants, whereas Greece, and Rome at its start, espoused the more “modern” ideals of meritocracy and “freedom.” John Siman, writing for nakedcapitalism.com, both interviews Hudson and reviews the book. Hudson tells him, about the various civilizations in Mesopotamia, “[These] societies were not interested in equality, but they were civilized. And they possessed the financial sophistication to understand that interest on loans increases exponentially, while economic growth at best follows an S-curve. This means that debtors will, if not protected by a central authority, end up becoming permanent bondservants to their creditors. So Mesopotamian kings regularly rescued debtors who were getting crushed by their debts.”

The Egyptians and the Israelites did this too, most likely. Pharaoh thought he could renege on the deal and keep the Israelites in permanent slavery. We are pretty sure the Israelites that came out of Egypt kept the rule and even codified it to be the Jubilee—every 49 years—even though they never had a great empire or a very powerful king.

The Angel of Death and the First Passover in Egypt.

I originally set out to write this piece as an examination of themes of refugees and victims of injustice in the context of winter holidays. I considered the story of Herod’s “slaughter of the innocents” and how that drove the Holy Family into refugee status in Egypt. I discovered this excellent piece about how Hanukkah became a holiday of special meaning for former refugees settling in America, and thus a specifically American style of Hanukkah developed. (See https://www.tenement.org/blog/our-american-holiday-refugees-and-the-meaning-of-hanukkah/.)

I also was intending to discuss how commercialization and greed (whether for presents, “fun,” or fancy foods) can totally corrupt and destroy these redemptive meanings of our most holy holidays. And how now, in a time of forced simplicity and inwardness, we might humbly recover and rediscover these fragile meanings.

So, I have mentioned all those things now, but something is still missing from the picture. I had been recently (for obvious reasons) ruminating on these themes of collapse and what Hudson calls the Clean Slate Amnesty. And I had this thought—what if many of our holidays, not just the winter ones, not just the Abrahamic religious ones, but our very concept of “holy days,” have a concealed meaning that points to a new (but ancient?) paradigm of freedom?

This is what Siman has to say to paraphrase Hudson’s conclusions about the post-800 B.C.E. misinterpretation of the idea of freedom:

“In ancient Mesopotamian societies it was understood that freedom was preserved by protecting debtors. In what we call Western Civilization, … just the opposite … has been the case: For us freedom has been understood to sanction the ability of creditors to demand payment from debtors without restraint or oversight.

Liberty menorah by

Manfred Anson

“This is the freedom to cannibalize society … the freedom to enslave … the freedom proclaimed by the Chicago School and the mainstream of American economists. And so Hudson emphasizes that our Western notion of freedom has been, for some 28 centuries now, Orwellian in the most literal sense of the word: War is Peace • Freedom is Slavery• Ignorance is Strength …

“… Our neoliberal notion of unrestricted freedom for the creditor dooms us at the very outset of any quest we undertake for a just economic order. Any and every revolution that we wage, no matter how righteous in its conception, is destined to fail.

“And we are so doomed, Hudson says, because we have been morally blinded by 28 centuries of … decontextualized history. The true roots of Western Civilization lie not in the Greek polis … but in the Bronze Age Mesopotamian societies…”

So, to get back to holiness and holidays, I am considering that for a holiday to have some deep connection to the ancient concept of Jubilee, or its equivalence in other lost civilizations, it has to have a message that privileges real freedom—i.e., freedom from want, fear or bondage—as opposed to the licentious freedom of enslavers and predators. So, any holiday about Jesus, with a slight stretch and a caveat, can qualify. The caveat is you have to consider the actual Jesus who said “forgive them their debts” and not revise that to merely meaning forgiving so-called “trespasses.”

Michael Hudson’s ‘…and forgive them their debts’

And another holiday that clearly qualifies is Passover, since it is literally about freeing people from bondage. (That’s why I don’t want to artificially restrict this to winter holidays.) But then again, both winter solstice holidays, and new year holidays—Rosh Hashanah, Tet, Saturnalia in ancient Rome, all the many new year days around the many cultures and calendars—all qualify too. Winter solstice and the beginning of a new year almost always have a powerful theme of what Hudson termed Clean Slate Amnesties.

I’m pretty sure the secular holy day of January 1, 2021, is going to be a time when many yearn for a Clean Slate. I intend to meditate and pray, to take out all my trash, sweep my floors and make lists. I will try to repair every flaw and breach in my life, and if anyone owes me any money (ha!) I am going to forgive them. But mostly I am sending up an intention and prayer that at some point, our “democratic” rulers get the message and proclaim a Jubilee, before it’s too late.

Because you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone.