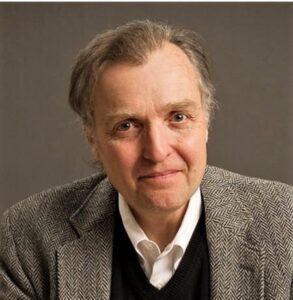

BY CAM GORDON

Cam Gordon

On Feb. 2, the City Council received a report on police department staffing that recommends steps the mayor and Council could take to improve public safety in Minneapolis.

The $170,000 study grew out of a City Council directive from 2019 and its results are reminiscent of the city’s 911/MPD Workgroup information that was presented then, and the final recommendations that were presented in November 2020 by the city’s Office of Performance and Innovation.

There is likely no one outside of City Hall who knows more about those recommendations than Andrea Larson, who was Director of Strategic Management at the time. Larson led the workgroup, made that presentation in 2020, and helped draft the request for proposals that resulted in the report the Council received from CNA Analysis and Solutions in February.

Today, living in Minneapolis and working in the private sector, Larson cares about the city and is happy to talk about the place she calls home.

The day the report came out she wrote on Twitter, “MPD utilization report came out, and it is later than we’d wanted, but also staff gave basically this same information on 11/13/19. Really hope the next step isn’t to keep studying the problem.”

The researchers reviewed all 1,794,408 calls made to 911 from 2016 to 2020. They found that roughly 500,000 of those calls were initiated by patrol officers themselves and the rest were calls for service from residents, businesses or visitors to the city. The study focused on the patrol division and the researchers were unable to analyze staffing in other police divisions, including investigations, because data on staffing levels and officer time use was not available.

One thing that stood out to Larson, she said, was that “the study reiterates that 27% of the volume of calls could move out of the MPD.”

The report broke calls for service into four subgroups. Most of the calls, 72.3%, fell into the category that require a licensed officer response according to state law. A much smaller number, 5.4%, were identified as calls involving a behavioral crisis that did not statutorily require a licensed officer response. A third group, theft-reporting calls, made up 5.6% of the calls, and the last group, making up 6.6%, included all other calls, like those involving animal complaints, to which an alternative agency or group could respond.

During the presentation, Zoe Thorkelson from CNA said, “If all behavioral health calls were taken off of the MPD response list, that would reduce the patrol staffing needs by 23 officers.” Adding the other two groups, theft-reporting and the other calls, could reduce the need by another 50, she estimated.

Although there was little data regarding other divisions, through observations and interviews the report concluded that since 2020, while the number of patrol officers was generally adequate, many other divisions, including investigations, were understaffed.

There was discussion at the meeting about the “discretionary” time that was estimated to take roughly 50% of the current patrol officers’ time, who generally work four 10-hour shifts a week. Discretionary time included any time spent not responding to calls, like patrolling, traffic stops and community engagement. The more discretionary time there is, the more officers are needed. If, for example, 33% of the time was spent responding to calls, the department should have closer to a total of 416 officers assigned to work in the patrol division to fill all the shifts. If 50% of their time was spent responding to calls, 278 officers would be sufficient. If their only assignment was to respond to calls, that number could be lower.

Committee members asked for clarity about what officers were actually doing during discretionary time and it was unclear if the department had any policy or guidelines on it whatsoever. There was no one from the mayor’s office or the Police Department available at the committee meeting to answer questions.

Larson said, “We want them to focus on those things that they are statutorily required to respond to.” She pointed out that non-licensed, or “civilian” alternative personnel doing some of the work would be less expensive, more efficient and “allows MPD to do the things they are supposed to be doing,” and that, “the fewer exposures MPD has to residents the less likely there is going to be a death.”

If there is funding, alternatives such as increasing (24/7) 311 staff to take theft reports, doubling the number of behavioral health response teams, using animal care and control staff, unarmed community service officers, or traffic control officers to respond to other low-risk calls have all been noted as possible options.

One of the big questions is, “How do we pay for it?”

The answer is likely one of three options: (1) cut services in other departments in the city; (2) raise taxes; or (3) take the money from the MPD. Larson prefers the third option, saying, “If MPD isn’t doing the work of responding to the calls, the cost of providing those services should move from MPD to the alternative responders so we’re not paying for the same services twice.”

This is more complicated, Larson observed, because, as this study also concluded, right now the department is understaffed and because of the charter provision that requires a minimum number of licensed officers. Larson admits that “the minimum offers a policy for residents to hold the city accountable” but believes that it is “old and rigid.” “The minimums were established in the ‘60s and were not based on data,” she said. “Continuing to implement policies set in the ‘60s is not helping us address the structural racism we find in our city today.”

While some hold a longer-term hope that deep cultural change is possible within the department, and others hope that this charter provision could be changed in the nearer future, Larson wants to see action taken now. “The mayor could actively work to move more work out of MPD,” she said, “and make sure police can focus on the work they are supposed to do.”