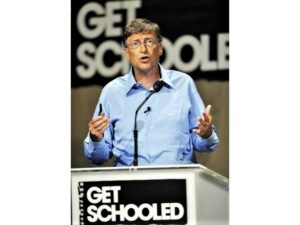

Bill Gates gets schooled

BY DEBRA KEEFER RAMAGE

We have come to a point in late-stage capitalism where a lot of the so-called philanthropy vying for well-meaning control of our lives is so inept, so blinkered by ideology, that it has become its own opposite. “Philanthropy” contains two Greek root words that mean, respectively, “love” and “human.” But, particularly in the subdivision of philanthropy that goes under the bland description of education reform, wherein you find the heavy-hitters such as Bill and Melinda Gates, the Walton family, and the current secretary of education, the love is for anything other than human, and the foregrounded humans in the equation, teachers especially, but also students and their families, get no love whatsoever and are treated as a problem to be ameliorated.

If students pay the ultimate price for this state of affairs (and they do), it’s teachers that bear the initial brunt of its idiocy. Case in point (but just one of many) is the recently concluded $45 million project of the Bush Foundation called the Teacher Effectiveness Initiative (TEI). In a brilliant post titled “How the Bush Foundation wasted $45 million and 10 years on an ill-conceived assault on teachers,” in his anti-ed-reform blog edhivemn.com, Rob Levine documents the chain of false assumptions, insane analogies, frantic midcourse corrections, and ham-fisted cover-ups that comprised the life cycle of this doomed venture, and ended with the current president of the foundation proclaiming, in the face of all rationality and facts to the contrary: “We [the Bush Foundation] are proud of what we helped to make happen!”

This is what they are proud of: In 2009, they introduced the TEI, promising several major goals. One of these goals was to “produce” 25,000 new “effective” teachers at institutions in Minnesota and the Dakotas, as measured by increasing test scores of students taught by the teachers and evaluated by an exclusive tool called the Value Added Model, or VAM, for which they had paid $2 million to a consulting firm, but had never tested. (Insane analogy, exhibit one: The VAM was based originally on a measure for increased production in animal husbandry!) The VAM proved to be so poor a metric that it was abandoned halfway through the project. (Frantic midcourse correction, exhibit two.) Based on a similarly unproven (later proven to be false) assumption that “effective” teachers were the main determinant of both poor student outcomes generally (do they just mean test scores there? pretty much, yeah) and the stubborn achievement gaps between demographic groups, two other goals were to drastically reduce the achievement gaps, and to increase college enrollment in the tri-state area by the barely credible number of 50 percent in that same 10 years. Long story short—both of these were total failures. The achievement gaps widened or stayed the same, and college enrollment just in Minnesota was down by 6 percent in 2017—a huge failure of the ambitious goal of going up 50 percent.

Bernie and Nina

I have to believe that there are some grantmakers whose gifts do lead to improvement, and that even when they don’t, it’s due to errors rather than bad intent. But the fact is that in education, and in the language now used about education, we don’t have a school “system” these days, we have a school “ecosystem.” The traditional public school system was a relatively closed one. You had your public schools: your elected school board, which was the executive; your teachers, who were employees; your students, who were recipients of a service called education; your taxpayers and legislators, who paid for it; and the assumed goals for everyone were the same: within the bounds of law (which included things like labor standards, health standards, racial integration, support for disabled and disadvantaged students, and rules against gender and other discrimination) to provide students with knowledge and skills needed for adult life. College was very much to be desired but optional. What do we gain by having an ecosystem? One part of that was always there, though acknowledged as an outside influence, rather like the political parties that put up the candidates that run the system, or levy the taxes, when elected—the teachers’ unions. Now both the political parties (although for Minneapolis and Saint Paul, this means only the DFL party) and the teachers’ unions (the MFT and SPFT respectively) are very much insiders, as their remits have extended far beyond collective bargaining and grievances into agitating for better policy and standing up, or failing to stand up, to private “reformers.” Nowadays the unions are almost more concerned with education policy than with wages, and perhaps the fact that, in Minneapolis, the MFT and the DFL seem to be joined at the hip is actually part of the problem.

The other players in the ecosystem are the many foundations throwing billions of private dollars into the mix, and wielding a massive amount of unelected power because of it. We are asked to believe in their beliefs about what’s best for our children. Because it’s philanthropy, a gift from the most fortunate to the most needful. If this gift were in addition to tax income, which does have some semblance of democratic control behind it, that wouldn’t be so scary. But it has played out to be displacing tax money, and the net effect is that the “ecosystem” is starving and its “public” side is shrinking, being displaced by the power of huge private funds. We know this by measuring what is being lost.

-Teachers

-Students

-Federal money

-Services—for the special needs student

-Services—enrichment such as arts and sports and STEM for all students

-College admissions

Education Reform (ER) critics identify 2010, the second year of the project, as peak ER in public policy. In the intervening nine years, as projects like this fail and the privatization of public education really starts to bite, opinions are shifting against it. Teachers’ unions in deep red right-to-work states are going on strike and winning. Minneapolis is finally forced to acknowledge that the steady erosion of student numbers, even as class sizes get bigger, is not a blip nor a mere demographic artifact. Every year we lose students, we lose head-count-based funding, on top of other purely ideological slashes. Teachers are deserting the system as well as students. One of the horribly exploited groups in the “ecosystem” to take up the slack is the ESP corps—Education Support Professionals—who comprise teaching assistants, child care workers, language assistants and translators, and many more of what used to be called “paraprofessionals.” There is currently a petition on Facebook trying to drum up public support for their imminent stand with their union, ESP Local 59 (a branch of MFT) to demand an overall wage adjustment. As vital as these workers are to embattled schools, they are overwhelmingly depending on public assistance or second jobs or both to survive, and the union claims a considerable number are even homeless. Most DFL leadership seems to be behind the union on this, and this would not have been the case a few election cycles back.

Whereas just 10 years ago, you would be hard pressed to find a DFL leader or liberal “influencer” who opposed ER, it is now becoming more common, in Minnesota and across the nation. I recently read a piece in The Intercept about Nina Turner, Bernie Sanders’ campaign chair. In 2012, she was an Ohio state legislator, leading the charge for the “Cleveland Plan,” a major showpiece of the ER agenda. Now, in a 180-degree turn, she is a chief architect of Bernie Sanders’ Thurgood Marshall Plan for Education.

While education policy in Minnesota and throughout the country will certainly continue to evolve with the constant changes and resulting shifts in the balance of power between government, unions, education officials, philanthropic foundations, and other players, it is clear that schools in every community—urban, suburban, rural—and of every permutation—public, private, charter, home—are here to stay and must learn to play nice together. If we stand back and watch from the sidelines, the spectacle that is U.S. education policy and reform can be an interesting game to observe and speculate on, maybe even place a wager on the outcome: in the decade to come, who will be up, who will be down? But ten years of education policy reform also equal ten years of a child’s life, taking them from, say, the age of 6 to 16 in their educational development. And nobody should be willing to gamble on that.