BY ELINA KOLSTAD

(Photo/metrotransit.org)

Anyone who has ever ridden the Route 21 Metro Transit bus, especially the stretch between Hennepin Avenue and Hiawatha Avenue, knows that it has some of the highest demand of all Metro Transit’s bus routes. The numbers bear this out. In the fall of 2018, Metro Transit reported over 10,000 average weekday rides on the 21, making it the second highest Metro Transit ridership route. And yet, we are only now seeing plans being developed to improve this transit corridor for the first time in decades. If we are lucky, in 2024 we will see B Line Bus Rapid Transit service begin, hopefully leading to faster and more reliable service. The preliminary estimated cost of the B Line is $54 million.

On the other hand, in 2009 the Northstar Commuter Rail Line was completed from Big Lake, Minn., to downtown Minneapolis. The total cost of the Northstar project was $317 million. In 2018, the same year that saw over 10,000 average weekday rides on the Route 21 bus, the Northstar Line saw 2,814 average weekday rides. We need to stop fooling ourselves that the law of supply and demand is the main factor that determines what public transit gets funding and how much.

The Northstar Line has always had disappointingly low numbers and in the wake of COVID those numbers have plummeted further still. The Northstar was built to be a commuter rail line, it’s right there in the title. It was built to bring people from Big Lake and the surrounding area into downtown Minneapolis to work and then home again. Nothing else. Not only was there basically only one destination, downtown Minneapolis, the line was only ever designed to take passengers to and from work.

I know someone who took the Northstar up to Big Lake when it first opened. He went up from Minneapolis in the morning, thinking that a train trip and some exploration of a small town would be a fun way to spend the day. He ended up in a park and ride lot in an area isolated from any amenities like cafes or restaurants and no indication of how to get to any. He waited a few boring hours before he could catch the next train to the city and never went back.

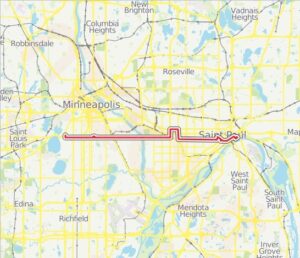

Route 21 Metro Transit from St. Paul and down Lake Street (Photo/moveitapp.com)

One might think that this is a story about how those who planned and built the Northstar mistakenly built a line that would ultimately fail to attract the ridership needed to sustain it. But what if this aspect of the design was seen as a feature, not a flaw?

In 2017, Bob Ivers, then running for mayor in Hopkins, said of the Southwest Light Rail Line, “The light rail to me is nothing but a tube that is going to bring nothing but riff raff and trash from Minneapolis.” He went on to state, “All the Chicago and Detroit riff raff who have moved into ‘Welfare-apolis,’ they are going to get on that train and you know where they are going to end up – at the Depot with yours and yours and yours granddaughters and grandsons.” Ivers followed this statement with, “Hopkins is 90% white, okay. The 10% coloreds and Mexicans and Asians who are here. Great. Bravo. But the problem is your little yellow train that you are all bravo about, you are going to have all the ethnics [sic] you want.” This man was actually wrong about how little diversity Hopkins has and only received a tiny percent of the vote, but looking at his comments and looking at the design of the Northstar Commuter Rail Line certainly makes one think: Why are all the Northstar stops outside of the urban centers of the cities they serve?

We need to stop fooling ourselves that our transit system works in a vacuum where the law of supply and demand is the only factor that determines which routes get funding and which routes take the back seat. Supply and demand doesn’t influence how frequent or reliable our transit is nearly as much as the skin color of those who ride it. If you still don’t think officials would purposely pursue a design destined to fail rather than allow “ethnics” from “Welfare-apolis” into their community, I would recommend looking into Heather McGhee’s book “The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together.”