BY ELAINE KLAASSEN

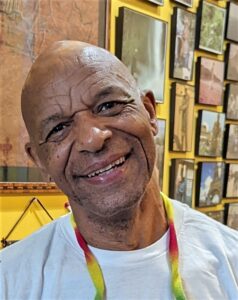

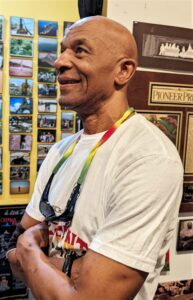

Steve Floyd

Steve Floyd is a man with a heart for others.

He has raised four children—the fifth is still under his supervision; he nurtures dozens of other youth through the Agape Movement and through his work as a mental health counselor at Change, Inc.; he makes award-winning photographs; he practices healthy living to support his transplanted kidney; he travels the globe; and he has connected to thousands over his love for basketball. There are so many areas that he tends to. His life is complex but not complicated. He exudes a rare serenity.

Co-founder of the Agape Movement, formed in the 1980s, Floyd has spent the past 40-plus years helping to bring love, safety, inspiration and opportunity into the community, particularly to former gang members as they find new paths for their lives.

Currently, Floyd goes out almost nightly with Agape members as they create a peaceful presence in the streets. There are always situations to deescalate. Agape also offers its nonviolent presence in the schools, replacing the armed police that used to patrol the halls until June of 2020 when the MPS board voted to cut its contract with the Minneapolis Police Department.

Floyd, who has been to Africa many times, organizes trips for young Black men to visit Senegal in West Africa through the Agape’s Rite of Passage program. Their latest trip was last October and November. Floyd takes them to see the shores from which captured Africans were shipped to North America. He knows how Black culture has been destroyed. His compassion for himself and those who share his history leads him to work toward healing.

Steve Floyd was born and raised on the south side of Chicago. His 17-year-old mother struggled, had no one to lean on, was abusive. His father drank a lot, went to Vietnam, was decorated for bravery, responded violently when he was called the N-word (he used a firearm to destroy property) and spent nine years in prison for it.

Steve grew up with three sisters and five younger brothers. Since their dad “wasn’t in the home enough to provide the guidance, love and care needed by six young men,” Steve, as the oldest, took on the task. He became the man in his brothers’ lives. His brothers were all “in groups the equivalent of gangs, but they didn’t call themselves that.” They were basically neighborhoods that fought other neighborhoods. Now, many years later, all of them have ended up OK.

Growing up, Steve always envied his friends who went home at suppertime because their dads would be there. He didn’t have a dad to go home to. One of the themes I’ve heard Floyd express a number of times is that he wants to provide his kids and other kids with everything he didn’t have.

Steve Floyd

As a kid, Steve lived for basketball. Just loved it. He loved the game so much that he got the idea to create a basketball court by burning down the family garage, which was in ruins and not in use anyway. Nobody was hurt and when the rubble was cleared his mother wondered what to do with all that space. Steve innocently suggested, “Maybe we could build a basketball court.” Years later it came out who was responsible for the fire, but by then it was water under the bridge.

In his junior year of high school Steve got cut from the basketball team, a political decision. He was so distressed he dropped out of school—on a Monday. That Friday he got into an altercation and “a bullet grazed my temple.” It scared him enough to start praying, and the next Sunday he went to church, which was all new to him because his family didn’t go to church.

The next day Steve went back to school. One day he was reinstated on the team.

He was invited to attend a church camp where he thought there would be basketball, but it was all religious. He didn’t behave very well at the camp, but then he started thinking about sin. He had stolen food stamps from his mom (even though he had used them to buy food for people at the park), he had set the garage on fire, and he was fighting all the time. At the camp he had stolen T-shirts and tried to let the horses out. His soul-searching led him to the conclusion that he didn’t like the church because it used fear to control people, but he liked Jesus. He decided he would change and follow Jesus’ teachings.

Floyd went to college at the Assemblies of God North Central Bible Institute in Minneapolis (now North Central University), where he studied theology and played basketball. He was all-American in basketball, and after graduation he stayed on for two more years to coach the sport.

Steve didn’t like the business aspect of the church, the corporate ladder. He was more interested in basketball—and helping people.

During college he had been inspired by country preacher David Wilkerson, whose book and later film adaptation, “The Cross and the Switchblade,” told of Wilkerson’s calling to go to New York City and bring love and hope to gang members there. Floyd was on his way to Detroit to do a similar kind of work when Pastor Art Erickson from Park Avenue United Methodist invited him to work with youth in the neighborhood.

Just as he was getting started as a leader of youth, Floyd’s father, who had never recovered from Vietnam, was beaten to death in Chicago, a murder that was never solved.

From then on, Floyd has used his considerable energy to nurture young people who might not otherwise have a chance. All the difficulties and tragedy of his youth were converted to a mentality of compassion.

At Park Avenue he saw many of the kids “drifting toward gang membership” and he wanted to get them out of their four- to eight-block area so he took them camping to Mexico, to Washington, D.C., and eventually to Africa. He wanted to show them other options. He knew from trips to Europe in college how much travel can change your worldview.

Floyd saw many needs that he responded to. He started doing presentations in schools about unconditional love (agape), in which he told funny stories about each ethnic group, making fun of the stereotypes, and then talked about all coming together to value each other. He presented a vision. “Kids would run out crying. It was hitting and challenging them where they were. Hundreds were marching in Agape marches,” he said. Now, in 2022, because of COVID, the assemblies have slowed down. In 1987 he started a basketball league called Youth in the City, followed in 1990 by another league that included other sports besides basketball: S.T.R.E.E.T.S. (Striving to reach educational excellence through sports).

In 1985, when the Disciples gang executed 16-year-old Christine Kreitz, who they thought had “snitched,” Steve found himself speaking on TV and radio. He was explaining that gangs formed because kids needed support and protection they didn’t get from adults in their lives.

Because of Floyd’s close association with gangs, he was under investigation by the FBI.

He joined The City Inc. where he started Champions of Agape, in which gang members from all different gangs worked together on life skills, went camping, took trips, built relationships. This valuable work was interrupted in 1992 when Police Officer Jerry Haaf was murdered by the Vice Lords gang.

From 1995 to 1998, the murder rate went up; there were three to four homicides per week. City Attorney Amy Klobuchar hired Steve to be an advocate for victims of gang violence and homicide because he had credibility with all gangs.

He would get calls to show up as police were putting up the yellow tape. His role was to calm people down and wait until the family arrived.

“It allowed me to understand the pain of mothers, the experience of delivering a child. It would get quiet, and you knew the mother was coming. The scream would be the same as the scream of giving birth. The hardest thing to do was hear the mother. I understood her pain. She had to get to her baby.”

He went through funerals and trials until one day he couldn’t stop crying. He went into a deep depression and his colleagues encouraged him to take time off. After that breakdown, he traveled a lot more and began his passion for photography. He had to get away from “dealing with so much homicide.”

Over the years he developed a deep connection to Africa and in 2017 considered moving there. When he first saw the slave houses in Senegal, it brought about a “change in his choices as far as Christianity went. Christians promoted slavery; they used the Bible and scriptures for control.” He moved away from organized Christianity and focused on “the rhythm of the universe, animals and plants as well as Jesus, his belief in humanity and serving humanity.” Floyd states, “Agape in action, that’s my religion.”