BY KAY SCHROVEN

Low-income communities, Indigenous communities and communities of color in Minneapolis (and many cities) experience unequal health, wealth, employment and education, and also are often overburdened by environmental conditions such as traffic and stationary pollution sources, brownfield sites (real property that may be compromised by the presence or potential presence of hazardous substance, pollutant or contaminant) blight and substandard housing.

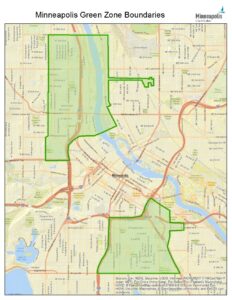

The idea for developing Minneapolis Green Zones (GZ) initiative came from the Minneapolis Climate Action Plan/Environmental Justice Working Group in 2012 (https://www2.minneapolismn.gov/government/programs-initiatives/climate/climate-action-goals/).Implementation began in 2015, and in 2017 the City Council adopted the Northside and Southside Green Zones – policy initiatives aimed at improving health and supporting economic development using environmentally conscious efforts in communities that face the cumulative effects of environmental pollution, as well as social, political and economic vulnerability.

Following the adoption of the Green Zone boundaries the Minneapolis City Council along with Mayor Frey appointed the Southside Green Task Force (since renamed the Southside Green Zone Council), made up of 16 individuals with various expertise in environmental matters, city planning, law, health and community representation.

The priorities of the GZC are improving air and soil quality, healthy food access, health in energy and housing intertwined with the social economic priorities of anti-displacement, self-determination and accountability. In short, priorities include investments in air, soil, food, housing and energy, with air quality a top priority.

The Southside Green Zones include the Phillips/Cedar-Riverside neighborhoods with high BIPOC representation (Black, Indigenous, people of color) in the communities. These zones were established in 2017 by the City Council. Since then the city has approved free home energy audits for Green Zone residents, inexpensive tree sales, and 20% reimbursement up to $40,000 for energy efficiency or pollution reduction for businesses through the Green Zone Cost Share program. While these efforts are commendable, they are not transformative.

The Green Zone Council established a Work Plan in 2019.The plan has 70 action items to achieve goals of healthy air and environmental quality, housing and economic success.

The Southside Green Zone work has been supported by a mix of city and private funding. In 2017 the city received $150,000 from the McKnight Foundation and Funders Network to support the Southside Green Zone. The City Council provided one-time funding for Green Zones in 2018 and 2019 through city budgeting. Continued support is needed. There is no law or ordinance with teeth that requires the City Council to continue the work. Kelly Muellman, Sustainability Program Coordinator for Minneapolis, says the Southside GZ Council is still learning about the best structure to support advancing initiatives.

The Southside Green Zone is supported by the City of Minneapolis Sustainability Division. The Sustainability Office has five full-time staff and is focused on integrating concepts into the other city departments and policies, while also leading efforts related to mitigating climate change. They also have a project in development with the Minneapolis Health Department toward using sensors to monitor air quality in Green Zones and gather data.

We want clean water and we

deserve the right to breathe

The East Phillips story is one of multiple environmental offenses and strong, sustained pushback by residents and activists. Home to Smith Foundry, Bituminous Roadways and the Roof Depot (seller of exterior building products including roofing, siding and windows near 28th Street. and Longfellow Avenue), the neighborhood struggle has been long and, as recently as Sept. 22, very disappointing. East Phillips is a diverse and polluted neighborhood. Seventy-one percent of residents are people of color and 45% earn less than $35,000 a year, according to Minnesota Compass. It used to be the site of CMC Heartland Partners Lite Yard. From 1938 to 1963 CMC leased the property to Reade Manufacturing which produced arsenical pesticides. In 1994, while constructing Hiawatha Avenue, arsenic was discovered and it was declared a Superfund site. Unsafe arsenic levels were identified in 600 neighborhood homes. By 2011, 50,000 tons of contaminated soil had been removed. In 2008 the neighborhood was classified as an “environment justice community” by the state legislature, citing high levels of asthma and other diseases linked to pollutants.

Dating back to 1991, the city has been discussing consolidating three sites into one and identified the Roof Depot as the site for demolition and new construction of a water distribution facility and maintenance operation with sewer and fleet services. The reasoning was that having services consolidated would make operations more efficient and reduce emissions from city trucks. The proposed $75 million project would include a jobs training center and a parking garage for 400 diesel vehicles that would be coming and going two times a day. The facility has been owned by the city since 2016 and still sits empty. The East Phillips Neighborhood Institute (EPNI) proposed an alternate plan with strong community input. It has come to be known as the Urban Farm Project. The group seeks to purchase the Roof Depot building as a community-owned and operated property, converting it into a multipurpose facility containing aquaponics, solar gardens, a communal kitchen, coffee and bicycle shops (since it’s near the Greenway) and affordable housing.

The discussions and disputes over these proposals have gone on for years and have become one of the principal battlegrounds for the environmental justice movement. There have been efforts to compromise, such as the city keeping 7.5 acres and giving the community three acres.This proposal infuriated lobbying residents. The city has spent $12.9 million in planning costs. And while the Policy and Government Oversight Committee stalled the project they fell short of granting the community activists development rights, leaving the Roof Depot temporarily in limbo and the city unsure of how to recoup the nearly $13 million.

Minneapolis is not the only city to fight the good environmental fight. Los Angeles has the Clean Up, Green Up ordinance. Kansas City has identified Green Impact Zones and has long-term plans to use federal stimulus funds. Buffalo, N.Y. has had its PUSH program (People United for Sustainable Housing) since 2008, identifying 25 square city blocks to be the focus of environmental improvement.

Hopes dampened

On Wednesday, Sept. 22, the Minneapolis City Council voted 7 to 6 to reinstate plans to build a new water maintenance facility in the Phillips neighborhood. The decision sent activists reeling. The plan sets aside several acres for community development, causing grave disappointment for lobbying residents who wanted to repurpose the entire site into the Urban Farm Project. Council Members Alondra Cano and Andrea Jenkins voted against the plan. Cano, who represents the Phillips neighborhood, said the decision is an example of the city being weaponized by shutting down conversations with a community trying to figure out its future. Council Member Lisa Bender continues to emphasize the budgetary impact of canceling the project which has already incurred $12.9 million. A representative of the Phillips community called it another example of the city using an underserved community as a dumping ground for the city and its pollutants.

Business as usual? The neighborhood says it will continue to fight, even if the city isn’t backing down.