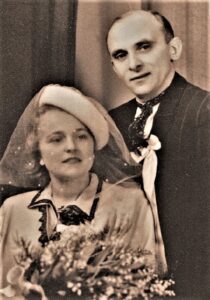

In the late 1940s, Anna and Wasyl Kramarczuk traveled from their beloved Ukraine to the U.S. in hopes of achieving the American dream and, after years of hard work, founded Kramarczuk’s.

BY LYDIA HOWELL

The Ukrainian language demeaned as a dialect, “Little Russian,” or censored; a beloved folk musical instrument suppressed; prison or death for poets, artists and dissidents since the 1860s – all these things have been done to maintain Russian domination of Ukraine. Whether under czars or Soviets, from Catherine the Great to Vladimir Putin, Russia claims Ukraine for itself, always suspicious of any assertion of an independent Ukrainian identity.

Since the 1880s, Ukrainians have come to Northeast Minneapolis, often in the aftermath of war.

“For us, the Ukrainian church is not only a religious center, it’s also a cultural and community center,” says Jackie Pawluk, Cultural Chair of St. Michael’s Ukrainian Orthodox Church board. Outside, the church is plain brown brick, crowned with a dome. Inside, the ornate architecture houses golden saints. Pawluk’s grandparents were among the founding generation of the church in 1925. “It’s our home where we socialize with many activities. After World War II, our cultural heritage was under threat due to Soviet occupation. Immigrants here really try to preserve the heritage and culture.”

That preservation entailed Ukrainian-American children and youth going to “Saturday School” to learn the Ukrainian language, as well as its poetry, crafts, folk dances and music.

The Kramarczuks immigrated to Minneapolis in 1947 – Wasyl, who had learned sausage-making from his brother, and Anna, with a German degree in business, began their landmark Ukrainian restaurant and deli, Kramarczuk’s, bordering Northeast and downtown. Since 1954, they’ve cooked Eastern European comfort food: dumplings (pierogi), cabbage rolls, giant meatballs, savory goulash, myriad sausages, and beet soup with breads and pastries like kolache.

Their son, Orest, who continues to run Kramarczuk’s, patiently explains Ukraine’s centuries-long fight to exist: “It’s not just not allowing the Ukrainian language – it’s obliterating the culture. It’s not about economics. It’s cultural genocide. It’s trying to erase the Ukrainian people.” His voice has a quiet power. “My parents and their generation tried to keep the culture alive because they feared something like what is happening now.”

As a youth, Orest went to Ukrainian Saturday School, as most Ukrainian-American youth still do. “The Easter egg tradition was brought over 100 years ago. Cultural gems have been preserved by the diaspora.”

Under Soviet repression, the tradition of hand-painting Easter eggs with distinctive Ukrainian designs, called pysanka, was lost. Immigrants running the Ukrainian Gift Shop, begun in 1947 in Minneapolis, continue the craft, sending designs back to Ukraine, renewing the tradition there.

Jackie Pawluk remembers those many Saturdays learning Ukrainian songs and dances, accompanied by instruments like the bandura. “The first wave of immigrants and first generation [born here] are very in tune to the culture,” she says. “Many people here have family ties to Ukraine – cousins, siblings, parents.” The Kramarczuks have brought cousins and nieces over for college here. Carrying on a tradition familiar to every immigrant group, they have helped “the newest Americans from Ukraine” by employing them at the restaurant.

The bandura, a big-bellied stringed instrument, fuses the lute and the zither. Bandura songs express ideals of faith, truth, human dignity and freedom. Beginning in 1928, bandura musicians faced persecution from Stalin, who banned traditional songs and performances, culminating in the mass execution of 300 musicians in 1934 during Stalin’s man-made famine (“Holodomor”) imposed from 1932-34, which killed millions of Ukrainians. Arrests continued under Nazi occupation. After World War II, most remaining musicians left for North America, with revival of ensembles since the 1950s. (www.bandura.org)

Observing that other Eastern European countries are next on Putin’s list, Orest Kramarczuk says, “Look at what has happened with this invasion: our country has come into focus. It’s forced people to watch horrors and to see how rights and freedoms are fragile and could be lost.” His voice rises. “Putin has tried to divide and conquer all over Europe. …The true strength of America is people come here from around the world.“

Ukraine’s incredibly fertile soil yields massive grain production, giving the country its nickname, “the breadbasket of Europe.” Ukraine is also a leading producer of oil derived from its national flower, the sunflower, which recently has come to symbolize its resistance to the Russian invasion. This upholds the story of an old woman giving a handful of sunflower seeds to a Russian soldier, saying, “Put these in your pocket. After you’re dead, sunflowers will grow.”

Sturdy-stemmed sunflowers, with their yellow faces upturned to blue skies, are the perfect symbol of the Ukrainian people.

Learn more about Ukraine atwww.historytoday.com.

The local Ukrainian community’s organizing of humanitarian aid has inspired established organizations and Minnesotans’ response. A Light (formerly American Refugee Committee, Minneapolis-based, since 1979) takes medical supplies, warm clothes and 1,000 blankets a day to the Ukrainian-Polish border. Chef Jose Andreas’ World Central Kitchen, known for responding to Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, feeds tens of thousands daily. Just as they went to Afghanistan to render medical help, Doctors Without Border now work under fire in Ukraine.

Find many local opportunities to help at:

www.StandWithUkraineMN.org

Alight, 615 First Ave. NE, Ste. #500, Mpls., MN 55413, https://wearealight.org

World Central Kitchen, 200 Massachusetts Ave. NW, 7th Floor, Washington, D.C., 20001, www.wck.org

Doctors Without Borders USA, Attention: Emergency Relief Fund, P.O. Box 5030, Hagerstown, MD, (217)141-5030, https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org

Lydia Howell is a Minneapolis independent journalist.