BY ELAINE KLAASSEN

The first oil pipelines were installed in 1853, in Canada. Rockefeller took over the oil pipeline industry in the U.S. toward the end of the 1800s on the East Coast and it spread from there until today, thousands of miles of oil pipelines cover the globe. The first electrification of buildings, ever, in the history of the world, took place toward the end of the 1800s in New York City. From then until now—a very short period of time—the entire world has become dependent on the comfort and efficiency our energy systems provide. During this intense period of development, human beings have plundered the Earth.

By 1950, the majority of U.S. energy came from fossil fuels—petroleum, natural gas and coal.

That worked fine for a while. Then in the 1970s we started hearing we might run out. That was our big concern. Shortly after that, the concern was the excessive carbon emissions caused by the use of fossil fuels as well as the methods used to extract them. So now, in 2019, we know that fossil fuels are no longer an option and our only chance is to somehow go to zero emissions.

The time to gradually wean ourselves off of fossil fuels would have been in the ’70s and ’80s when the news first came out about what fossil fuel emissions were doing to our atmosphere and environment. But that didn’t happen. Commerce, industry and government by and large have been lagging behind.

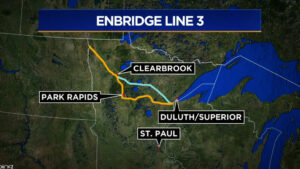

The company that owns and operates the six oil pipelines that crisscross northern Minnesota, Enbridge Energy, Limited Partnership, based in Alberta, Canada, is only just now thinking about gradually getting away from fossil fuels. On its website, the company talks about gradually reducing the amount of fossil fuels in use, but they are talking extremely gradually. Otherwise they wouldn’t be trying to substitute a new line for one of their northern Minnesota oil pipelines, Line 3, which was built between 1962 and ‘65, and is wearing out, becoming too expensive to repair, and potentially dangerous. In 2014, instead of terminating the line, the company made plans to build a new line to replace the old one. It was going to be 36 inches in diameter rather than 34 and would follow a slightly different route through Minnesota, adding 55 miles, but would end up at the Superior, Wis., terminal, like the current (old) Line 3, and from there, as usual, the tar sands crude oil would be delivered to refineries in the Midwest, eastern Canada and the Gulf Coast.

———-

Environmental activist Akilah Sanders-Reed has been involved in opposition to the new Line 3 since the beginning. Her dedication to saving the environment is complete, from her college degree in environmental studies and history, to her work with MN350 and The Power Shift Network, to her many hours of environment-related volunteer work.

She explained her many reasons for opposing the new Line 3, as well as the old Line 3, which is currently operating at half capacity:

1) Enbridge wants the last leg of the replacement to follow a new path, between Clearbrook, Minn., and Superior, Wis., instead of following the existing mainline route shared with several other Enbridge pipelines. The problem with clearing the new path, which has already started, is that it is cutting through forests, destroying pristine wilderness and natural wildlife habitats.

2) The old line is already disrespectful of Native lands and dishonors treaty rights. The new line, although not going through Indian reservations, would go through land used by Indigenous people for ricing, a major source of livelihood. Already Indigenous people say the ecosystems are changing and they can’t do traditional practices. [As I understand it, traditional practices mean working with nature, while the high level of industrial development practiced by the West means controlling nature. Those two mentalities are incompatible.]

3) If and when the new line is finished, the old line would be left in the ground, harmful and hazardous. Minnesota, unlike Iowa, has no laws that regulate the method of deactivating an old pipeline.

4) Young people with pre-existing mental health conditions are being impacted by the destabilization brought to their northern Minnesota environment as pipeline construction goes on.

5) The possibility of spills and leaks that would poison the water and damage the soil is always there. There have been many oil spills from equipment installed less than 10 years prior to the leak. Greenpeace reported that over the past 15 years, Enbridge averaged a leak every 22 days.

6) Why take the risk of spills when the demand in Minnesota is down 18% in the last 20 years, and Minnesota refineries are running at capacity. And, as more climate policies are enacted, the demand will continually drop.

———-

In April 2015, Enbridge applied to the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission (PUC) for a “certificate of need” and a “route permit.”

Over two years, 2015 to 2017, the Department of Commerce held numerous public meetings and public comment periods to get input and feedback. It went through various drafts of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), and on August 17, 2017, it released the final EIS, a 13,500-page document. A comment period was open until October 2, 2017, to receive comments on the adequacy of the final EIS. Sanders-Reed said that “from start to finish, the Department of Commerce was adamantly opposed to the new Line 3.”

In another part of the process, Akilah Sanders-Reed was present every day for three weeks of hearings in the Office of Administrative Hearings (OAH). “When something really big and complicated is contested, it is delegated to a judge in the OAH, in this case Judge Ann O’Reilly, who oversaw public hearings in a three-week-long process,” Akilah said. The judge, instead of the PUC commissioners, listened to the testimony of experts, such as the Youth Climate Intervenors, Honor the Earth, Friends of the Headwaters, five tribal governments (Red Lake, White Earth, Mille Lacs, Fond du Lac, Leech Lake), Sierra Club, the Northern Water Alliance, land owners from the affected counties, and the Minnesota Department of Commerce.

After three weeks of listening, Sanders-Reed said, the judge had to read the transcribed pages and make a recommendation to the PUC. Judge O’Reilly recommended, in April 2018, that it was not legal to permit Enbridge to build the new Line 3—the proposal costs were too high for society.

Enbridge’s report of the proceedings notes only the ruling of a second administrative law judge, who deemed the Final Environmental Impact Statement “adequate.”

Next, Sanders-Reed was present at a second set of hearings, in June 2018, held by the PUC commissioners for five eight-hour days over a two-week period. In these hearings, the five PUC commissioners asked questions of the parties, the same people Judge O’Reilly had listened to, plus members of the general public.

Sanders-Reed said there were about 30 people present in each of these sessions. Also, 94% of the public written comments that came in were opposed to the new Line 3.

At the end, the five PUC commissioners approved the new Line 3. “We have to stick to the law even though it’s not what we believe,” they said, according to Sanders-Reed. She related that as they relayed their decision, two of them broke down in tears because of their concern about the old pipeline, over which they have no authority: The question before them was only about the new pipeline. The commissioners said they felt like they had a gun to their heads and if they didn’t give Enbridge everything they wanted, Enbridge would continue using the old, broken down and dangerous pipeline. Kate O’Connell from the Minnesota Department of Commerce said Enbridge’s arguments were extortion of the state.

Just now, on June 3, 2019, the Minnesota Court of Appeals ruled that missing from the 13,500-page EIS is a study on the impact of a spill in the Lake Superior watershed, which must be supplemented before the new pipeline can again be considered.

Walker Orenstein in MinnPost, June 4, wrote, “The court sided with a coalition of tribes and environmental nonprofits in reversing a decision by the state’s Public Utilities Commission. The ruling may delay Enbridge’s progress toward building the $2.6 billion project.”

More obstacles to the pipeline’s completion appeared Tuesday, June 18. Minnesota Public Radio reported: “Enbridge’s proposed Line 3 oil pipeline replacement likely could see more delays, after two state agencies involved in the project said Tuesday [June 18] that the permitting schedule for the pipeline needs to be revised.”

———-

“I believe the scales are tipping,” says Akilah Sanders-Reed. “The movement is winning over this extractive industry that’s hurting people.

“Keystone 10 years ago said it was a done deal, and it’s still not built. Five years ago, two other tar sands pipelines were canceled—Energy East and Northern Gateway, in Canada. Enbridge had another project out of North Dakota, Sandpiper Pipelines, which was stopped in the courts.

“[Activists who make a difference] are always a small group, not the majority. It’s a big and powerful group, but relatively small. The group who chooses to stake out a claim on what was once considered impossible, doesn’t have to include all the people.

“I really do believe there are enough people who are motivated enough to build the movement.”