BY TOM O’CONNELL

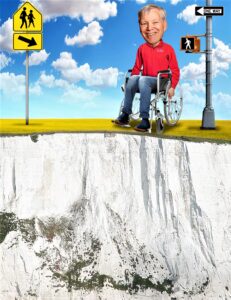

“Curb cut: (noun, North American) A small ramp built into the curb of a sidewalk to make it easier for people using strollers or wheelchairs to pass from the sidewalk to the road.”

– Lexico.com

I never paid much attention to curb cuts until a few years ago. Fact is, I don’t think I even knew the term. That’s because the short downward distance from sidewalk curb to street was of little consequence to me. I could hop down or scramble up with hardly a second thought. Until I couldn’t.

Now that I have a wheelchair, curb cuts have become even more important.The six inches that separate sidewalk from street might just as well be six feet if you are in a chair. Without the cuts, what is for most a throughway stretching from my Northeast Minneapolis condo to the city limits would be for me, and many others, disconnected blocks separated as if by moat from the houses and shops just across street.

Not that I especially want to walk or wheel to the city limits. But even if the destination is the neighborhood grocery store, barber shop, coffee shop or pub, it doesn’t take a Jane Jacobs to realize that curb cuts make urban life possible for lots of people who would otherwise miss out on what a vibrant urban community has to offer.

So, who invented curb cuts anyway? How widely are they in use? Does Minneapolis have more curb cuts than St. Paul? Do we have professional urban planners to thank for curb cuts? Or were curb cuts a response to citizen demand?

I don’t have the answer to all of these questions, and lucky for me, this is a commentary, not a research paper. When I googled “curb cuts” I did learn a few things though. As I expected, curb cuts were a response to the emergence of a disability rights movement in the 1960s and ‘70s. And as was often the case, one of the early scenes of engagement was Berkeley.

Ed Roberts was a wheelchair-using graduate student at Berkeley. He founded an organization called the Rolling Quads. Stories began circulating about squadrons of wheelchair riders wielding sledgehammers and applying bags of concrete in a do-it-yourself approach to public works. The Berkeley City Council responded with a policy mandate supporting curb cuts in all major commercial areas and designating 15 specific corners for immediate remediation.

The Quads were part of a developing national movement that eventually led to the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990. When the legislation appeared stalled in the House of Representatives, disability activists crawled out of their chairs and up the Capitol steps. Good thing the Cold War was over; the Soviets could have scored some major propaganda points out of those images.

Despite my obvious self-interest in the matter, I never became a disability rights activist. Shortly after graduating from college, when I was trying out my role as a ‘60s-era “movement leader,” I got a call from John St. Marie. John had been my roommate as a kid when both of us spent long months at Gillette Hospital along with scores of others who had come down with polio. St. Marie relied on an iron lung to breath. He had it much worse than me, yet through gulps of air he kept up a cheerful banter and a relentlessly hopeful outlook on life.

I hadn’t spoken to John for years when he tracked me down and wanted to know if I would be interested in joining this new organization he was helping get off the ground. It was called the United Handicapped Federation. I thanked John for thinking of me but told him that I was simply too involved in other activist causes to have any energy left over for this.

The truth, of course, was more complicated. From the time I was a kid up until then (and up until now) I have chosen not to identify as a handicapped person. I figured that whatever oppression I experienced from my disability was a personal matter and a trivial one at that. Racism, sexism, classism, imperialism – now those were the real deal!

Older, if not always wiser, I’ve now added curb cuts to my list.Too bad we don’t have a more poetic word for this and so many other elements of our urban infrastructure that make city life possible for so many.